Comment

Buenos Aires during the Falklands war

Monday 11 December 2017

I had covered a few wars for Reuters but did not anticipate an unusual occupational hazard in Argentina during the 1982 Falklands war with Britain.

I had covered a few wars for Reuters but did not anticipate an unusual occupational hazard in Argentina during the 1982 Falklands war with Britain.

Several British and US television journalists were kidnapped by gunmen and left in the outskirts of Buenos Aires without their clothes and equipment.

The streets became risky for foreign journalists as Argentine military intelligence agents responsible for the disappearance of many alleged enemies of the right-wing regime roamed the city in unmarked cars. I took basic security precautions, taking a different route each day from the hotel to the office and not hopping into the first taxi that came along.

Reuters Correspondent David Cemlyn-Jones, a bearded Irishman, was not bothered. He said he had lived and worked in Rio de Janeiro and was never mugged. His Spanish wife Ana commented: “That’s because he dresses like the muggers.”

Life on the surface looked normal in wartime Buenos Aires. Restaurants served spaghetti bolognese not with minced beef but chunks of prime steak. In a popular tango nightclub, a band of old men played old favourites like La Cumparsita but the dance floor was virtually deserted. Shortwave radios for listening to the BBC were in great demand. A diplomat offered to buy at thrice the price a Sony I had picked up at the airport duty-free shop when I arrived.

As anti-British feelings rose, Reuters requested police protection and guards were posted outside our office.

The few British correspondents who stayed on in Buenos Aires frequented our office to transmit their stories to London or to read the news. As they walked in, one guard would quietly ask our Argentine staff who the visitor was. When told it was The Times correspondent the guard muttered: “We’ll strangle him.” When the Daily Telegraph man came, the guard growled: “We’ll throw him out of the window.” The Daily Express: “We’ll beat him up.” It was scary but none of these threats was carried out.

My notebook was filled with background data about the war in case our office was closed down and I had to operate from my hotel room. Working long hours, I comforted myself with the thought that it was better to be in Buenos Aires than on a ship like my brave colleague Leslie Dowd who was with the British task force sent to retake the Falkland Islands from the Argentinians.

With David and me in the Reuters team were two Frenchmen - Claude Regin and François Raitberger. France was loved in Argentina because it had supplied the planes and Exocet missiles that became the scourge of the British fleet.

I went to a press conference called at short notice by the Argentine military junta. It was like a school reunion. Amid hugs and cries of “Hola manito”, I met journalist friends from Mexico and Central America I had not seen in years. A former Reuters colleague, Roland Dallas, was also there representing The Economist.

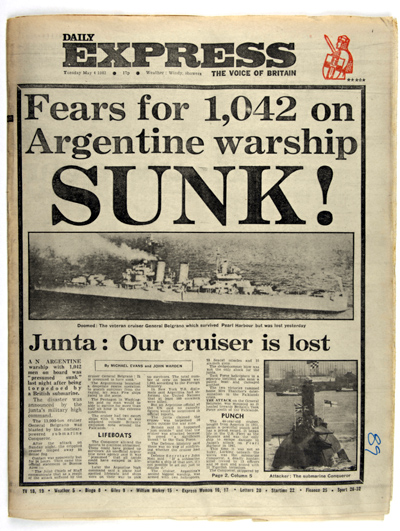

Then the lights dimmed and the captain of the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano recounted how his ship had been torpedoed and sunk by a British submarine. More than 300 of the 1,000 crew perished, some in fires that broke out on board and others frozen to death in their lifeboats.

The jolly atmosphere suddenly turned sombre. It dawned on us that a real war was going on in the South Atlantic and that many more men would die.

A few days later, before the fiercest battles for the Falklands began, I left Buenos Aires. I was glad to get back to my interrupted assignment in Madrid organising Reuters’ coverage of the 1982 World Cup. Fortunately England and Argentina had not been drawn to play each other in Spain.

PHOTO: Daily Express front page reporting the sinking of the General Belgrano. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 680 of 1807