People

Looking back: Laos and Vietnam revisited

Tuesday 9 August 2016

The first time I flew into Vientiane was aboard a Royal Air Force cargo plane with seats facing the rear. It was a good introduction to a backward kingdom that was living in the past. I had come from Manila and caught the plane at Bangkok’s Don Muang airport as it loaded relief supplies for a traumatised city after the battle for Vientiane in December 1960. I had been sent to relieve Reuters correspondent Bruce Russell who witnessed the fighting between the rebel paratroopers of Captain Kong Le and the forces of right-wing General Phoumi Nosavan. Kong Le’s men were driven out of the capital.

The first time I flew into Vientiane was aboard a Royal Air Force cargo plane with seats facing the rear. It was a good introduction to a backward kingdom that was living in the past. I had come from Manila and caught the plane at Bangkok’s Don Muang airport as it loaded relief supplies for a traumatised city after the battle for Vientiane in December 1960. I had been sent to relieve Reuters correspondent Bruce Russell who witnessed the fighting between the rebel paratroopers of Captain Kong Le and the forces of right-wing General Phoumi Nosavan. Kong Le’s men were driven out of the capital.

That was the start of my annual trips to Vientiane from Bangkok where I was posted in 1962. Christmas 1960 was a sad and uncertain time in Vientiane. With clouds of war over Laos, many foreigners had fled to Thailand. The head waiter at the restaurant of the Hotel Constellation, where foreign correspondents stayed, had a bulging back pocket which contained all his money, ready for a quick evacuation if the fighting resumed.

The Hotel Constellation, also known as Hotel Constipation among the foreign press, was owned by Maurice Cavalerie, a charming French-Chinese entrepreneur who had run import-export businesses in Hanoi, Dalat and Saigon. He was always glad to oblige foreign newsmen and would ask, when you settled your bill, what amount he should put on your receipt. His barman would stack up the drinks bills and when he had collected enough he would tie them with a rubber band and ask the people around the bar: “Whose turn is it to have this lot?”

It was easy to make money on the black market. The unofficial rate for the Laotian kip against the US dollar was usually five times more than the official rate. Luxury goods were cheap for foreigners paying with kips bought on the black market. All the Indian shops on Vientiane’s Samsenthai main street were happy to change dollars at the black market rate. I bought a couple of cameras in Vientiane cheaper than in Hong Kong or Singapore.

But the lure of the currency black market was not enough for some. The Agence France-Presse man, whose family got fed up with Laos and returned to Paris, tried hard to get expelled by writing negative stories about the government. But each time he was about to be thrown out there was a change of government. AFP had another problem. One AFP correspondent decided to investigate why he was constantly being beaten by AP, Reuters and UPI. After handing in his copy at the post office, he went to a window at the back to observe. He saw one telegraphist read his cable and then hand it to the next man. It was transmitted only after all six telex operators had read it. AFP was filing in French - the only foreign language understood by the Laotian telegraphists who were trying to keep abreast of the latest news.

The post office messengers had an uncanny way of tracking you down. A telegram was once delivered to me at the Vieng Ratry nightclub at 9 pm. After the battle for Vientiane the post office was closed and we had to cross the Mekong river to Nong Khai in Thailand to transmit a story. Another way of sending out news was by courier to Bangkok. Airline passengers were sometimes treated to the sight of 20 or so correspondents furiously typing away at the airport lounge to catch the Royal Lao flight to Bangkok. The Japanese correspondents were a competitive, divided lot. The Asahi Shimbun reporter once asked to put his dispatch with mine in a sealed envelope for the departing Yomiuri correspondent to take to Reuters Bangkok. I do not know how the Yomiuri man found out but he politely declined to take my envelope unless I removed the Asahi stuff.

Coalition negotiations in the Plain of Jars in northern Laos between rightists, neutralists and the communist Pathet Lao were a logistical challenge for the foreign press who were allowed to fly there on planes of the ICC (International Control Commission) consisting of Canada, Poland and India. Peter Arnett of AP and I volunteered to stay behind to organise the transmission of news to the outside world. At the airport we nearly busted a gut heaving a latecomer, the enormous Richard Hughes of The Sunday Times, aboard the DC3 after the ladder had been removed. When the mailbag arrived from the Plain of Jars we made sure that the AP and Reuters dispatches were the first to be transmitted.

I spent about a month each year in Vientiane. Some newsmen could not bear to stay that long. After AP and Reuters reported government air raids on the Pathet Lao in the north, one British newspaper correspondent eager to return to the home comforts of Hong Kong was queried by his office. He cabled back: “Agencies unreliable rebasing Hong Kong as scheduled.” His editor replied: “Since agencies unreliable please stay Laos.” Most of the time we relied on stringers or part-time reporters to cover for us. We once had a Shan princess stringing for Reuters in Laos. In Phnom Penh our stringer was a Frenchman who was one of Prince Sihanouk’s speech writers. He knocked on my door at the Monorom Hotel at 6 am one fateful morning to announce: “Kennedy est mort.”

From my Bangkok base, I often flew to Saigon to stand in for Reuters correspondent Nick Turner when he was off base or to help out during times of crisis. The government of President Ngo Dinh Diem disliked negative foreign press reports on the progress of the war. Diem’s lobbyists in Washington derided the Saigon press corps as too young and inexperienced to give an accurate picture of events. But four among us went on to win the Pulitzer Prize - David Halberstam of The New York Times, Malcolm Browne and Peter Arnett of AP and Neil Sheehan of UPI. Had he been working for an American outfit, Nick probably would have won a prize for his reporting of the 1963 battle of Ap Bac, the Viet Cong’s first major victory. He drove to the fighting 40 miles from Saigon and even helped to evacuate wounded government soldiers. Reuters’ Vietnamese reporter Pham Xuan An was widely regarded as the most well-informed journalist in Saigon. He held court at our office in the Vietnam Press Agency compound, receiving a string of callers, many of them peasant women with conical hats, whom he introduced to me as relatives, friends or friends of friends.

Towards the end of 1964 I was told to take over the Saigon bureau after Nick resigned and An left Reuters to join Time magazine. It was a hectic period. The US started bombing North Vietnam and the first American and South Korean combat troops landed. There was talk of China entering the war like it did in Korea 15 years before. I felt it was time to move on and left Saigon in 1965 for the greener pastures of Europe and Latin America. In London I was asked by Reuters managing editor Stuart Underhill, worried about the mounting cost of the Saigon operation, if the US military build-up meant the war would end soon. No, I said and recalled An’s view that the Viet Cong would see it as a sign of growing US impatience. The war raged on for another 10 years. After the communist takeover in 1975 An was officially identified as a Viet Cong intelligence colonel and I realised that many of his visitors had probably been Viet Cong couriers.

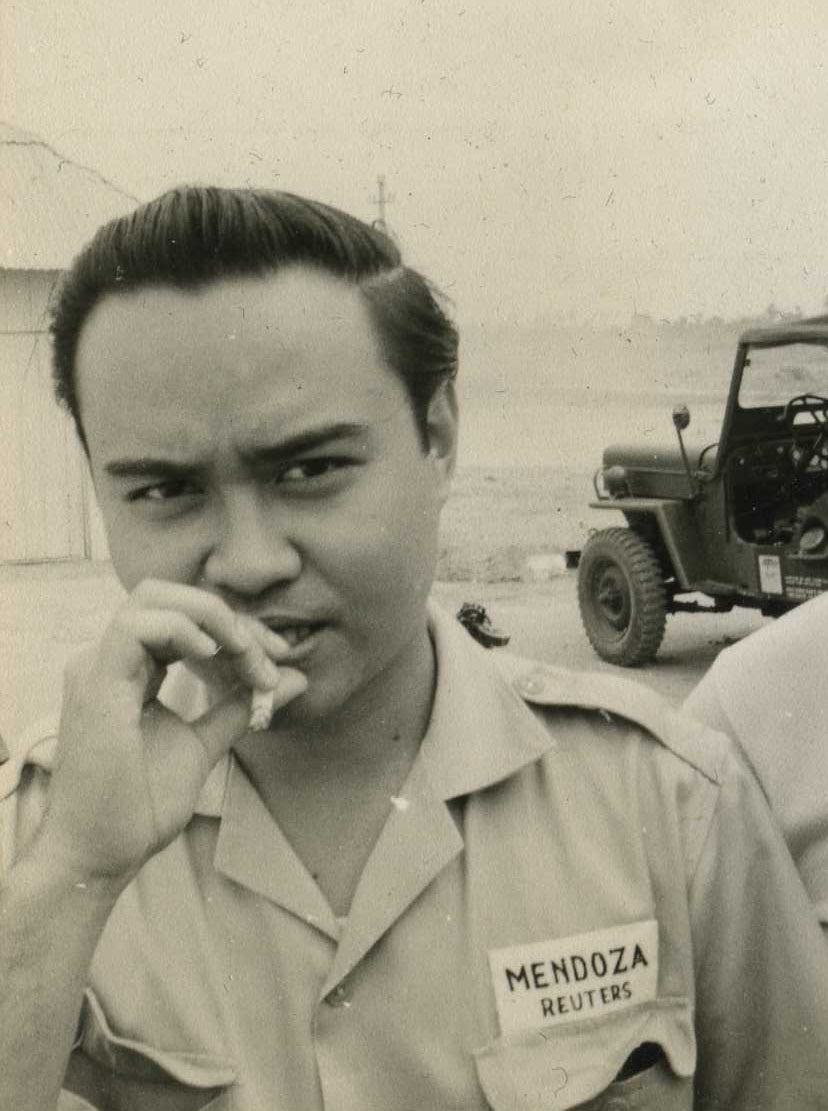

PHOTO: Ernie Mendoza during his time in Saigon.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 227 of 535