Archives

Dr Davies, I presume

The Goddess of Fate could not be said to have always been on the side of Julius Reuter during the early years of his career. Setbacks and discouragements there were many, as well as blind alleys which led nowhere. But, once or thrice Fate balanced the scales by sending along someone whose influence would be long-lasting and without whom the Reuters of the next 150 years might never have happened.

The Goddess of Fate could not be said to have always been on the side of Julius Reuter during the early years of his career. Setbacks and discouragements there were many, as well as blind alleys which led nowhere. But, once or thrice Fate balanced the scales by sending along someone whose influence would be long-lasting and without whom the Reuters of the next 150 years might never have happened.

Clementine Magnus, who became Julius’s loyal, intelligent and level-headed wife, was one such person. Heinrich Geller, pigeon fancier and innkeeper of Aachen, was another. The third was Dr Herbert Davies. Herbert Davies was a very nice man. When he died in January 1885 his obituaries made a point of it. His niceness had played a pivotal role in providing Julius and Clementine Reuter with both a new home and a London platform from which they could begin to grow their fledgling business.

In our continuing story of the Reuters, Herbert Davies counts as our third unsung hero. A “London Welshman”, Davies was born in 1818. His father was a physician at the London Hospital in Whitechapel. Herbert entered there as a student and later studied medicine at Cambridge, obtaining his MD in 1848. He then went on to Paris and Vienna for three years before returning to the same London Hospital, first as Assistant Physician and then as Physician.

We know that Julius and Clementine Reuter were in Paris in 1848 to 1849. Readers of A Tale of Two Cities, the second part of this series, will have read of Reuter’s employment with Charles Havas and his subsequent short-lived news agency venture of his own. We also know that Austrian-born Sigmund Engländer - later to become Reuter’s right-hand man and chief editor - was active in Vienna during 1848. He was a revolutionary journalist who fled to Paris under threat of arrest in that “year of revolutions”. Engländer also obtained employment with Havas.

Did Davies meet the Reuters and/or Engländer during his time in France and Austria? Within the Davies family the long-remembered story was that the friendship grew from a chance meeting in a continental railway carriage. Davies had suggested to Reuter that he try his luck in London, and had offered the couple accommodation in his own house.

It can be assumed that Davies had gained at least a working knowledge of French and German, the two languages in which Julius was at that stage most comfortable and proficient.

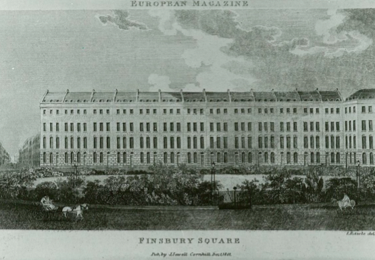

By 1851 Davies, a Christian, was married with a young son. Later, he was to have two more sons and three daughters. The Davies family lived in comfortable circumstances at 23 Finsbury Square, an easy walking distance from Reuter’s office at 1 Royal Exchange Buildings. At some point late in 1851 or the very early part of 1852, Julius and Clementine Reuter joined them as lodgers.

For Julius and Clementine, this move was to have important consequences. Firstly, not only did the couple begin to perceive themselves differently; others began to see them differently.

In 1845, during their first visit to London, the couple had lodged in Bury Street, close to the walls of Bevis Marks Synagogue, an almost exclusively German and Jewish residential quarter. Interestingly, the middle class Finsbury Square neighbourhood, long established as popular with doctors and medical men, was also popular with Jewish businessmen. Residence there meant that the Reuters (Julius was a Christian convert) were taking a first step into what would then have been seen as a more mainstream and conventional English environment while, at the same time, remaining within Julius's Jewish comfort zone. For the rest of their lives, even when living later in opulent Kensington Palace Gardens, this pattern was to continue – as, indeed, it did so in the case of Jewish/Christian convert Benjamin Disraeli, Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1852, who would later serve twice as Prime Minister. Julius found himself at precisely the right time and in the right place to ride a new wave in Victorian England.

Julius found himself at precisely the right time and in the right place to ride a new wave in Victorian England

This is the moment when Herr and Frau Reuter leave our stage. Enter, for the first time in their place, Mr and Mrs Reuter. Increased Englishness brought business benefits. But the couple gained another very important benefit from their new friendship.

When Clementine became pregnant in the summer of 1851 the couple were childless. We know that a daughter Julie had been born to them in July 1846 but died soon afterwards. During the intervening years it seems likely that further pregnancies resulted in either miscarriage or the child’s very early death. Five months pregnant when the couple opened their Telegraphic Office in London on 14 October 1851, Clementine was delivered of a healthy baby boy on 10 March 1852, at 23 Finsbury Square, with Dr Herbert Davies in attendance. The boy, who was named Herbert after the doctor, would grow up to succeed his father as Head of Reuters. During the next few years the Reuter couple would go on to have another two sons and three daughters, almost certainly with Davies in attendance.

During her pregnancy Clementine would have benefited enormously from living in the house of an exceptionally well-qualified physician who was aware of the latest medical ideas and procedures. His attendance will have meant that any problems or complications could be dealt with quickly. In mid-19th century London, medical care of this standard would normally have been beyond the financial means of a couple such as the Reuters.

Did the young doctor perform some minor surgical operation on Clementine which reduced her difficulties with childbirth? Possibly.

Gradually, the Reuters became more prosperous. They left their lodgings at number 23 but remained in Finsbury Square, moving a few doors along to number 41. Later, they moved again - to number 19.

In 1857, Reuter applied for naturalisation as a British subject. His first friend in London, Dr Herbert Davies, together with Davies’s doctor brother, Henry, and two other Finsbury Square medical practitioners, vouched for him.

Later in the century, when it had become a public company, Reuters took the decision to appoint a medical officer.

The man selected was Herbert’s son, Dr Arthur Davies.

PICTURE: Finsbury Square as it appeared in 1801. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 26 of 49