Haunts

Vietnam War haunts are now for dong millionaires

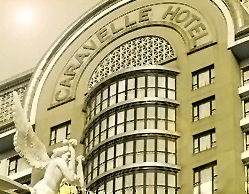

The bars of Saigon were home for two generations of war correspondents, the reporters who covered the French and American conflicts. They offered an essential interlude between forays out of the city to the battlefields of Vietnam. Some of them were hotel bars, others back street dives. The older ones, like the Continental and the Majestic, figured in novels of the French Indochina War, by writers such as Graham Greene and Jean Lartéguy. Later the Caravelle became the American media headquarters. One of the attractions of the most popular bars was their rooftop location: at times of crisis in the city they became vantage points for viewing the action. Now they are luxury leisure scenes for rich tourists.

The old drinking haunts of war correspondents in Saigon are now firmly embedded in the luxury global tourist circuit, at prices no local hack could ever afford.

A recent investigation on behalf of The Baron established that the great wartime bars are alive and well, flourishing as capitalist outposts in communist Vietnam. After years of austerity, they are raking in the dollars again, just as they did in the old days.

Only the customers are different. Instead of hard-drinking foreign correspondents on expenses, the visitors sipping cocktails on the rooftop terraces these days are well-heeled travellers on upmarket tours, or passengers from cruise liners moored in the Saigon River. They are just passing through. They are not media and they’re not resident. In fact, there have been no resident Western media here since the end of the American war in 1975. The Vietnamese authorities allow foreign journalists to be based up north in Hanoi, the politically correct capital, but not in this bustling commercial city, with its dodgy black market morals and potentially subversive politics.

the great wartime bars are alive and well, flourishing as capitalist outposts in communist Vietnam. After years of austerity, they are raking in the dollars again, just as they did in the old days

It’s an odd experience to be back here as a tourist - and a local currency millionaire. Our first bill for a round of drinks for four people in one of these luxury bars, the Caravelle, came to over a million dong - an impressive 1,054,053 to be exact. That’s “only” $62, which may not be too expensive in the upper reaches of New York, but then you realise that it would buy an awful lot of pho (noodle soup) and other good tasty food in the open air restaurants and hawker stalls which most Vietnamese frequent.

So, for a few million dong, here’s a quick tour of some old watering holes, with a few memories. I’m sure that other Reuters Vietnam vets can add to the file.

It’s still one of the leading hotels (five stars) and it still has a rooftop bar, now called the Saigon Saigon. It describes itself as the best bar in Ho Chi Minh City, which may be true, although the Majestic is a close runner. The bar still overlooks the centre of the city, but as you try to focus on the old memories there’s something wrong. It’s the building itself. The hotel was partly re-built in the 1990s. The bar is now at the top of a new tower block, probably quite a lot higher than before. The view is spectacular and you can sit up there with a sophisticated cocktail, in a glitzy lounge, serenaded by a Cuban band (fellow Communists) and pick out old landmarks such as the Roman Catholic Notre Dame Cathedral (unchanged), the Opera House (the old National Assembly, refurbished) and the Reunification Palace (the old South Vietnamese presidential palace, now a museum).

It’s still one of the leading hotels (five stars) and it still has a rooftop bar, now called the Saigon Saigon. It describes itself as the best bar in Ho Chi Minh City, which may be true, although the Majestic is a close runner. The bar still overlooks the centre of the city, but as you try to focus on the old memories there’s something wrong. It’s the building itself. The hotel was partly re-built in the 1990s. The bar is now at the top of a new tower block, probably quite a lot higher than before. The view is spectacular and you can sit up there with a sophisticated cocktail, in a glitzy lounge, serenaded by a Cuban band (fellow Communists) and pick out old landmarks such as the Roman Catholic Notre Dame Cathedral (unchanged), the Opera House (the old National Assembly, refurbished) and the Reunification Palace (the old South Vietnamese presidential palace, now a museum).

During the war, the Caravelle was very much the American media bar. A number of leading US TV networks and news organisations rented offices in the hotel, so the bar was in a sense their canteen. US television anchormen and newspaper pundits held court there - and decided the course of the war. It was a hard drinking place: whisk(e)y, gin and dry martinis, nothing very sophisticated. It was also a comfortable lookout post when there was trouble in the city, such as the 1968 Tet offensive and the final North Vietnamese assault on Saigon in 1975. Several Pulitzer Prize winning reports were written, it is alleged, mainly from the vantage point of the Caravelle bar.

Just across the Opera House square from the Caravelle, but always a world apart. The Continental was favoured by French and other European correspondents, as well as the more cosmopolitan Americans. It was the most traditional of the great Saigon hotels, home at various times to André Malraux and Graham Greene. After the Communist victory, it was closed for a decade and then renovated. It now rates just three stars. The French colonial architecture is intact but much of the style has been swept away, together with the grand old bar where we used to gather. The new bar on the first floor has a big snooker table but little charm, so we made our excuses and left.

Just across the Opera House square from the Caravelle, but always a world apart. The Continental was favoured by French and other European correspondents, as well as the more cosmopolitan Americans. It was the most traditional of the great Saigon hotels, home at various times to André Malraux and Graham Greene. After the Communist victory, it was closed for a decade and then renovated. It now rates just three stars. The French colonial architecture is intact but much of the style has been swept away, together with the grand old bar where we used to gather. The new bar on the first floor has a big snooker table but little charm, so we made our excuses and left.

The memories came back, though, as I walked through the courtyard, virtually unchanged, and along the spacious corridors. I remembered my very first night “in country”, in a first floor bedroom at the hotel. Some time before dawn I was woken by a tremendous rattling of the old windows. I thought it must be an earthquake. When I asked about it at breakfast, I was told, with a shrug, that it was just a routine B-52 raid 30 miles away in a “free fire zone”. Good morning, Vietnam.

I also recalled the old hotel terrace, a favourite haunt for a few beers and some gossip. It was the scene of one of my most embarrassing moments. Germaine Loc, a Reuters local reporter, had asked to see me to discuss something important, outside the office. We met for morning coffee on the terrace. She announced that she was leaving Reuters for a U.S. network job. Then, to my surprise and embarrassment, she burst into tears and started sobbing on my shoulder. Germaine, some of you will remember, was a strikingly attractive young woman. She had already caught the eye of the other customers, mostly hung-over American construction workers on their first beer of the day. As I looked around, not quite knowing how to deal with the situation, I saw that we now had their full attention. I knew exactly what they were thinking. Another poor guy with bar girl trouble.

The terrace is now glassed in and houses an up-market Italian restaurant, Venezia. I had already been here once since the war, on my first return visit to Vietnam in 1994. On that trip, I invited the late Pham Xuan An to lunch. An had been one of the best informed Vietnamese correspondents in Saigon. He worked for Reuters in the early days of the war and then for an American news magazine. He was also, it emerged later, one of the Vietcong’s best undercover agents, honoured after the communist victory as a Hero of the Revolution. When I asked him at that lunch about his work as a spy, he replied: “Not a spy. I prefer to say I was an analyst.” (see Analysis of a Spy in Frontlines: snapshots of history published by Reuters and Pearson Education Ltd in 2001).

Another grand old French colonial hotel, on the Saigon River. The rooftop bar was also a favourite with the war correspondent crowd. It was at its best at night, when you had a grandstand view of sporadic action in the darkness across the river. Glass in hand, you could judge the tempo of the war by the level of “contact” out there: the odd salvo of VC mortars, shelling by distant American artillery, bursts of machine gun fire from circling U.S. helicopters. Sometimes the show would be enhanced by parachute flares floating slowly down to earth, fitfully illuminating the flat countryside. If only all war reporting could be so comfortable.

Another grand old French colonial hotel, on the Saigon River. The rooftop bar was also a favourite with the war correspondent crowd. It was at its best at night, when you had a grandstand view of sporadic action in the darkness across the river. Glass in hand, you could judge the tempo of the war by the level of “contact” out there: the odd salvo of VC mortars, shelling by distant American artillery, bursts of machine gun fire from circling U.S. helicopters. Sometimes the show would be enhanced by parachute flares floating slowly down to earth, fitfully illuminating the flat countryside. If only all war reporting could be so comfortable.

These days the rooftop bar is popular again, with the same type of clients as at the Caravelle, and similar prices. The hotel itself has been splendidly restored. One of its proud publicity claims is that it used to be “frequented by foreign correspondents and espionage agents”. The Saigon River is lined with illuminated floating restaurants geared to the tourist trade. There is even a supper cruise on a junk called the My Canh, the name of an earlier floating restaurant blown up by the Viet Cong in 1965 (48 dead). And across the river at night, there’s just darkness.

Not a bar in the old days, but the building we all remember as the seat of JUSPAO, the Joint US Public Affairs Office - the accreditation centre and the stage for the Five O’Clock Follies, the daily military briefing on the progress of the war, American style. The rest of the building at that time was a U.S. BOQ, bachelor officers’ quarters. I remember one night when the residents started shooting at random from the windows after the building was hit by a Viet Cong bomb squad.

Not a bar in the old days, but the building we all remember as the seat of JUSPAO, the Joint US Public Affairs Office - the accreditation centre and the stage for the Five O’Clock Follies, the daily military briefing on the progress of the war, American style. The rest of the building at that time was a U.S. BOQ, bachelor officers’ quarters. I remember one night when the residents started shooting at random from the windows after the building was hit by a Viet Cong bomb squad.

Now the Rex is a first class hotel with a roof terrace bar and restaurant. It offers similar views to the Caravelle, but also Disney style elephants and other theme park animal statues. We decided not to stay for drinks.

Along the street there’s still a corner coffee shop called Brodard, but it’s now an air-conditioned branch of the Gloria Jean chain, selling cappuccinos and Danish pastries to tourists. A far cry from the days when it was a smoky French café where hacks and spooks traded the latest gossip. Then it was part of “Radio Catinat”, a network of rumour mills named after the central street that the French called Rue Catinat. The South Vietnamese authorities re-named the street Tu Do (freedom) and the Communists changed it again to Dong Khoi (uprising). The old name Catinat lingers on over a modest hotel, midway between the flashy Caravelle and the grand Majestic.

And finally, what about the notorious girlie bars that used to dot the streets of Saigon, where a lonesome Western guy, military or civilian, was rated “number one” or “cheap charlie” according to how many glasses of “Saigon tea” he bought for his hustling hostess? Well, I was on a family trip this time, with wife, son and daughter-in-law, so research was somewhat limited, but I saw no signs of dens of iniquity. The communists closed down all the obvious ones and sent the bar girls to work in the countryside. All I can report is that the girls around town now are as pretty as ever, still zooming around on scooters like migrating birds. Sadly, however, they no longer sport the long flowing ao dai national dress. Jeans, t-shirts and bomber jackets are the national costume now, as everywhere else. Globalisation rules.

■