Haunts

Alpine refuge from reality in the Paris of the East

The most striking element in the illusion of Austrian Alps refuge from the civil war reality of tension on the streets of Beirut was the bleak personality of the owner of Myrtom House, a tall, thin man with cropped blond hair who was rumoured to have served as a model for an iconic Hitler Youth bust. He presided over the big timber bar with an air of gloom and foreboding and if you ever wanted a pessimistic viewpoint on the latest Middle East crisis, would provide a ready-made doomsday quote.

Myrtom House was always a refuge from reality. In the good old days, when Beirut was the Paris of the East, it was simply a bar where you could escape from the summer heat. Later, as Lebanon descended into civil war in the mid-1970s, it became a kind of safe haven from the tension in the streets outside. By simply walking through the front door, you could change worlds: from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Austrian Alps.

Myrtom House was always a refuge from reality. In the good old days, when Beirut was the Paris of the East, it was simply a bar where you could escape from the summer heat. Later, as Lebanon descended into civil war in the mid-1970s, it became a kind of safe haven from the tension in the streets outside. By simply walking through the front door, you could change worlds: from the Eastern Mediterranean to the Austrian Alps.

It was a powerful illusion, created by several different factors. First was the abrupt drop in temperature as you went inside. The air conditioning was constantly set at somewhere close to zero. Then there was the absence of any outside light or sound. Even before your first drink, this made it easy to believe in the alpine chalet decor of wooden plank walls and mountain scenes framed in the blacked out windows. Supporting evidence came in the form of German lager, wurst and wienerschnitzel.

All this was important, but the most striking element in the illusion was the bleak personality of the Austrian owner. Hans Maschek* presided over the big timber bar with an air of gloom and foreboding. He was a tall thin man with cropped blond hair. Rumour had it that, as a boy, he had served as model for an iconic Hitler Youth bust. As far as I know, no one ever asked him if this was true. Certainly his political views were far to the right of anything tolerated in the post-war German world. And if you ever wanted a pessimistic viewpoint on the latest Middle East crisis, Hans would provide you with a ready-made doomsday quote.

The most striking element in the illusion was the bleak personality of the Austrian owner

Ian Macdowall, my predecessor as bureau chief in Beirut, introduced me to Myrtom House on the first day of our brief handover. A useful refuge from the office, he said, and a place to solve staff problems. The Macdowall method, when tensions flared between our local colleagues, was to take one or other of the most belligerent down to Myrtom House for a drink, separately. I was happy to use the same technique from time to time. A sudden trip to this ice cold country across the road, coupled with a few rounds of gin and tonic, would sooth even the rumbling volcanic temper of the legendary Zaim (the chief): Khadr Nassar, one of our senior Arab deskmen, a bear of a man who could have doubled for Anthony Quinn.

Myrtom House was a good place to meet other foreign correspondents. As violence mounted ahead of the civil war, it became ever more useful as a clearing house for news and rumours. When a bomb exploded outside the Reuters office, smashing all the windows, shocked staff retired there to recuperate. At some point during the fighting in Beirut, the building itself must have been destroyed or damaged by a bomb or shelling.

All I know is that when I went back some years later, during a lull in the civil war, I dropped in to Myrtom House and found myself strangely disoriented. The air temperature was still cool, the style was still Germanic, but the layout was completely changed. The bar was not where it used to be, and, most importantly, Hans was not presiding over it. Some said he was away on leave, others that he had gone for good. It was not the same without him.

Robert Fisk of The Independent, another old Beirut hand, wrote this in 1999:

Did I see a woman burning to death outside the Myrtom House restaurant? I know I did, back in 1983; a woman trapped in her vehicle after a car bombing, cremated alive in front of our eyes as a young French soldier tried to tear off the door, leaving just a skeleton, the skull turned accusingly towards us. But I stand on the same road today and cannot believe my memory. There are brand new glass-fronted tower blocks on one side of the road, a repainted school and an international bank on the other, the highway resurfaced so that no trace of shrapnel remains. Only my memory holds the truth. Thus is history erased as Beirut is rebuilt.

Beirut boasted then as it still does today that you could ski in the morning in the mountains a short drive outside the city, return in time to swim in the Med in afternoon, shop at luxury brand stores in the evening and gamble at the Casino du Liban at night, all of which had nothing at all to do with its popularity as a base for monitoring the Arab world. Besides the obvious creature comforts, Beirut quite simply offered better communications than any other spot in the Middle East, so Western correspondents naturally chose to make it their home.

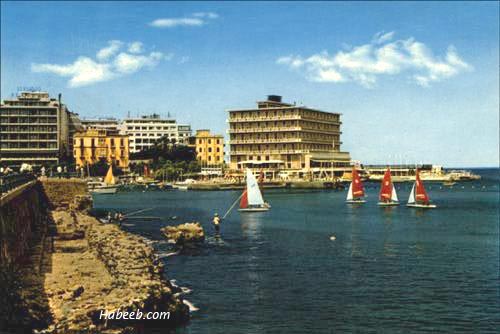

The Hotel St George, spectacularly located on the waterfront (photo), was one of the most famous alternatives to Myrtom House. Jim Hoagland of The Washington Post, Juan de Onis of The New York Times and John Cooley of the Christian Science Monitor were regulars at the bar. Outside, possibly the best situated swimming pool in Beirut was the place to observe Lebanon’s beau monde, foreign airline crews, and the occasional hack. The St George was destroyed during the internecine warfare of the 1970s but has now been rebuilt.

Kim Philby divided his drinking time in Beirut between the St George and the Normandy Hotel, further along the seafront, until his defection to the Soviet Union in 1963. Eric Rouleau of Le Monde held court a few blocks away at the bar of the Excelsior Hotel, another favourite of the foreign press corps.

The Excelsior was the scene of a painful incident involving the redoubtable Granville (Bob) Watts. We were relaxing there one evening after a long day covering clashes between the Palestinian fedayeen and the Lebanese Army. Bob, in lively argument with some fellow hacks, punched one of the padded leather panels beside the bar to make a particularly forceful point. Unfortunately, the decor was not as plush as it looked and his fist hit concrete. In some pain, he called for an ice bucket, plunged his forearm into it and carried on with his argument. He was staying at the hotel so after a while I left him to it and went home.

Bob didn’t appear in the office the next morning. The hotel reception told us he had gone to hospital. He turned up later, somewhat subdued, with an impressive plaster cast up to his right elbow. He explained that he had eventually gone to bed, feeling no pain, not even in his damaged but by then deep-frozen hand. When he woke up, the hand was black and blue, fully thawed out in the morning sunshine, and very painful. At the hospital they found he had broken several bones. Bob spent the rest of his stay in Beirut brandishing his cast menacingly in the Excelsior and other watering holes.

Bob had a knack for ending up the worse for wear. In a dispute with another foreign correspondent in Cyprus he was thrown into a swimming pool. He joined Reuters as an experienced agency journalist from The Associated Press. Besides foreign postings, he served as a London-based “fireman” for many years. He retired in 1988 and later died in India.

Can any old Middle East hands add to the Beirut bar file?

*Hans Maschek died in 2010 in Nice.

■