Archives

How Reuter lost the race to report the Gettysburg address

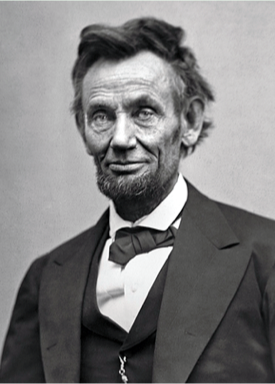

150 years ago, at the Consecration Ceremony of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Pennsylvania on Thursday 19 November 1863, US President Abraham Lincoln delivered a two-minute speech that would resonate down the years as one of the greatest orations in American history - the Gettysburg Address. Reuters archivist John Entwisle examines Paul Julius Reuter’s role in getting news of it to Europe.

Paul Julius Reuter should have been the first to relay the text of Lincoln’s famous speech to London. Infuriatingly, that distinction went to a rival agency, the Electric and International Telegraph Company.

Paul Julius Reuter should have been the first to relay the text of Lincoln’s famous speech to London. Infuriatingly, that distinction went to a rival agency, the Electric and International Telegraph Company.

What went wrong?

It was a dark night in early December 1863. At the farthest south-west point of Ireland, Reuter’s small steam-tender sheltered in the lee of the Fastnet Rock. Out of the gloom, with a deafening clunking of paddle-wheels, a vast steamer appeared. As it neared the smaller boat, several canisters, each one lit by a phosphorous flare, were dropped overboard into the sea far below. The steamer continued on its way, and the sound of its engines receded back into the darkness. Meanwhile, on the smaller boat, men grabbed long poles with nets attached and began fishing around for the canisters which still bobbed on the waves. As it swung round to return to the nearby little port of Crookhaven, two clerks below deck unscrewed the tops of the canisters and began sorting the messages inside.

At this date, Reuter’s chain for conveying news between the United States and Great Britain was state of the art. But it had one weak link. Reuter had no control over which news was selected for passing on to his agency in London. Under a news exchange agreement with the Associated Press of 195 Broadway, New York (now an address of Thomson Reuters), the news was supplied by the AP. This meant that an AP sub-editor decided which stories to send.

Lincoln’s speech was transcribed verbatim by AP’s reporter at the scene. But the AP did not give it to Reuters. Did its sub-editor think that the British would not be interested? Indeed, was he aware, at that early stage, of how interested Americans would be? Or was it simply that he did not give the same thought and attention to his selection as a Reuters employee might have done?

In 1863 there was no transatlantic cable. News between the United States and Great Britain was carried partly by steamship and partly by land-based telegraph lines.

In only the previous year, Reuter had renewed his news exchange agreement with the Associated Press. The agreement specified that the AP would send political exclusive, commercial and other news by every mail steamer out of New York. Each news summary must fill two printed columns. Later news, in condensed form, was to be telegraphed ahead for putting on board outgoing vessels some days later as they passed “remote” ports such as St Johns, Portland, Halifax or Cape Race. The AP also sent a brief abstract ready for Reuter’s agent at a British port of arrival to telegraph onwards to London. Abstracts were to total not less than 2,000 words per week.

In the other direction, Reuter contracted to send a news summary to New York of all important intelligence which may reach him from any part of Great Britain, Ireland, the Continent of Europe, India, China, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, or from any other place. He would also supply a brief abstract with every summary, and would telegraph abstracts of late news to his Irish agents at Queenstown, Galway and Londonderry. These were placed on steamers before setting off west across the Atlantic.

Major news - such as Lincoln’s election as President - was handed over as vessels passed the Irish northern or southern coasts. But fuller news had to await the ship’s arrival in Liverpool, Falmouth, Plymouth or Southampton. Reuter’s agents then telegraphed AP’s brief abstracts to London and sent on by train fuller dispatches, together with the American newspapers. Thus big American news broke in stages - first a striking fact, later more details, then - later still - background and reaction.

During the American Civil War the British public eagerly awaited the arrival of every steamer. It was hungry for accounts of battles lost and won, news of cotton prices, information about American grain and other commodities, and New York money and stock market quotations. As well as providing information to his British press and commercial subscribers, Reuter also supplied it to the Havas and Wolff agencies, respectively in Paris and Berlin, and to his agents and subscribers overseas. Indian merchants were particularly interested in cotton. Many were poised to make fortunes by selling locally grown cotton to the Lancashire spinning mills in place of the shortfall from the southern Confederate states.

In business, no advantage lasts long. The London newspapers, while continuing to keep their subscriptions to Reuter’s service as back-up, really wanted to publish their own “exclusive” reports. And so each chartered its own boat to intercept incoming American steamers as the vessels passed Roche’s Point, County Cork, before moving up-river to Queenstown harbour. “Extra early” news was then quickly telegraphed from Ireland to London.

Reuter was losing the race. Bold action was needed.

Arranging for his rivals’ boats to be secretly scuppered was not a viable business option. But four or five vital hours could be gained if the steamers could be intercepted when first spotted from the Irish coast. Somehow, in 1863, he obtained permission to build a private telegraph line from Cork to Crookhaven, a distance south-west of more than 80 miles.

Reuter was denounced by the Cork Examiner as a “clever foreign speculator” intent on “monopolising the American news” – which, of course, he was. The West Carberry Eagle found strong local support for “this telegraph king” who offered hope of revival for an area which had suffered dreadfully in the potato famine of the 1840s. In the event, Reuter’s personal financial involvement with the telegraph line lasted less than a year. Looking ahead, he could see that it would have only limited value once a transatlantic cable had been successfully laid.

Reuter’s telegraph line opened at the very start of December 1863 and was fully operational in time to have handled Lincoln’s famous address.

But any news supply chain, however carefully planned, is only ever as good as its weakest link. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 12 of 49