Archives

Location, location, location

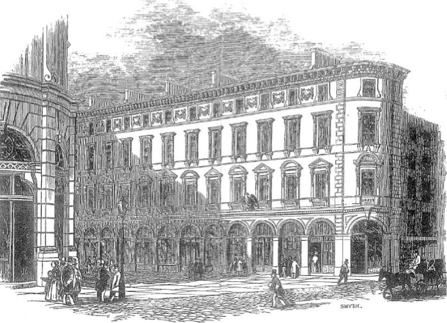

In 1851 Francis Moon was on the “up”. A leading publisher of prints and engravings, a sheriff of the City of London and on his way to becoming Lord Mayor in 1854, he leased a number of offices in Royal Exchange Buildings, a smart new edifice behind the newly rebuilt London Royal Exchange. Constructed around 1847 (re-built 1906-1910), the Buildings comprised one of the world’s first purpose-built office blocks, offering on the ground floor elegant arcaded shops which echoed those of the Exchange itself. This was prestige property.

In 1851 Francis Moon was on the “up”. A leading publisher of prints and engravings, a sheriff of the City of London and on his way to becoming Lord Mayor in 1854, he leased a number of offices in Royal Exchange Buildings, a smart new edifice behind the newly rebuilt London Royal Exchange. Constructed around 1847 (re-built 1906-1910), the Buildings comprised one of the world’s first purpose-built office blocks, offering on the ground floor elegant arcaded shops which echoed those of the Exchange itself. This was prestige property.

Julius and Clementine Reuter sub-leased one of these offices, 1 Royal Exchange Buildings, from Moon (who himself leased from the owner and developer of the property, Magdalen College, Oxford).

The 14th October 1851 - opening day for Reuter’s Telegraphic Despatch Office - was a Tuesday. The tenancy may have been no more than weekly, or perhaps monthly. Monday may have been set aside for setting up the office which, for the Reuters, meant little more than ordering some stationery and some coal for the fire. Advertisements had been placed in The Daily News and possibly some other newspapers. Mr Julius Reuter’s Telegraphic Despatch Office was ready for business.

Readers of my earlier articles will know that Julius and Clementine had arrived in London from Ostend on 14 June. Precisely how they had filled in the intervening four months may never be known. We do know, however, that their earlier friendship with the Davies family had flourished and that by this time they were probably already installed as paying guests at 23 Finsbury Square, an easy walking distance away. The couple recruited Fred, aged 11, as office boy. This was FJ Griffiths (1840-1915) who was to spend a lifetime with Reuters, becoming company secretary in 1865 until 1890 and subsequently a director until 1912.

In later years Julius liked to recount the story of how he had gone out for lunch to a nearby chop house (19th century equivalent of a fast-food burger bar), which he could barely afford. Fred rushed in to say that a “foreign-looking sort of gentleman” had called to see him. Julius asked the boy why he had let the man go. “Please, sir, I didn’t” came the answer. “He is still at the office. I’ve locked him in”. Thus was secured one of Julius’s first customers.

Reuter relied totally on someone running backwards and forwards to the offices of all the private telegraph companies, both to collect telegrams addressed to him and to dispatch them

However, we have here a case where time and reminiscence have perhaps selectively embellished the picture to create an image undoubtedly picturesque but not the whole truth. The oft-used phrase “opened an office consisting of two small, dark rooms” creates an impression of a modest, perhaps rather shabby-genteel operation. Small the rooms may have been, dark they may have been (perhaps because they were at the back) but they were situated in a cutting-edge building in a cutting-edge location. Reuter may genuinely have felt that he had to keep luncheon expenses modest but he had no illusions about location, location, location. From the start of his business venture in London he prioritised his resources towards getting this aspect absolutely right.

And absolutely right it was.

The early 1850s were an era which saw the start-up of a huge number of electric telegraph companies. Many disappeared without trace almost immediately; many amalgamated; a few grew and prospered. This was a new industry for a new era, very similar to the large number of dot.com companies which appeared suddenly and out of nowhere in the early years of the Internet. As a new occupation which required large numbers of staff with high manual dexterity, it was one of the first areas which offered respectable employment to young women and we can see that Clementine Reuter’s unusual role as a close co-worker with her husband was both leading and riding a new (and very revolutionary) wave. However, technology had only reached so far. There was no question of telegraph lines being introduced into most private offices. Reuter relied totally on someone running backwards and forwards to the offices of all the private telegraph companies, both to collect telegrams addressed to him and to dispatch them. This was where Fred (and Clementine) came in.

An examination of the business directories for the period makes abundantly clear not just the number of telegraph companies by then in existence but how geographically close they all were. About 60 of them were clustered around Old Broad Street, Threadneedle Street and Cornhill - all within sight of each other around the Royal Exchange. Positioned in 1 Royal Exchange Buildings, the Reuters had (amongst many others) the British Electric Telegraph Company directly opposite in the Royal Exchange itself, the International Telegraph Company also in 1 Royal Exchange Buildings and Gamble & Nott’s Patent Electro-Magnetic Telegraph Office next door in 2 Royal Exchange Buildings. Across the road in Cornhill were to be found the British & Magnetic, the European (& American), and Watson’s General.

This was the mid-19th century’s Canary Wharf business district of London.

As we have come to know Julius and Clementine it has become evident that careful choice of location was central to their thinking. They always did their homework. As far as their private address was concerned, a personal friendship with Herbert Davies combined most fortuitously with the fact that respectable Finsbury Square was a district particularly favoured by prosperous Jewish businessmen with whom social and business contacts could be made and developed. As far as their business address was concerned, an office actually in Royal Exchange Buildings - even a cheaper one - was the only place to be. There they were surrounded by virtually all the telegraph offices and businesses then operating in Britain. What all these people didn’t know about telegraphy and about every new technical advance and newly completed line wasn’t worth knowing. The Reuters were not running a solitary telegraph-related business, bravely operating in virtual isolation. They were attempting to carve a specific niche for themselves within an already overcrowded industry.

How could the Reuters have afforded an office (albeit a cheaper one) within such a prestigious building? This question is difficult to answer except to say that they had to. If they couldn’t be within three minutes of the Royal Exchange then, as far as London was concerned, there was no point in being anywhere. Although Clementine was pregnant, they had no children at this point so there were only two mouths to feed. They poured all their available resources into their business premises rather than setting up a separate home for themselves. We have also always understood that, following their low-key success in Aachen which gave them some capital, the couple had secured backing from the Erlangers, a prominent Jewish banking family from Frankfurt who had also converted to Lutheranism.

PICTURE: Royal Exchange Buildings as it appeared in the Illustrated London News in the 1840s. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 28 of 49