Archives

The press censors and the Reuter Armistice Bulletin of 7 November 1918

Monday 10 July 2017

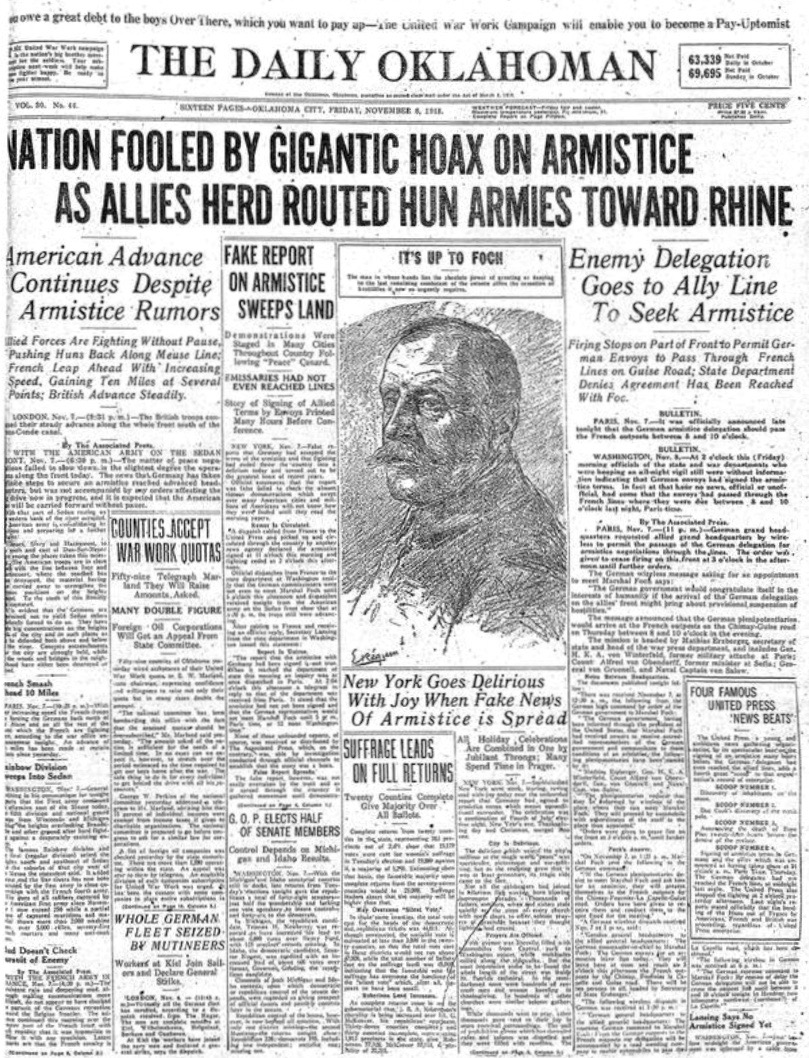

Just before the end of the First World War, the directors of the Official Press Bureau - Britain’s press censors - referred the Reuter news agency and the Press Association to the Director of Public Prosecutions for breaching wartime regulations by spreading false information about the war. Specifically, it was for reporting that an armistice had been signed with Germany on Thursday 7 November. This was covered in a previous article Reuters and the False Armistice of 7 November 1918.

The following article presents a more detailed account of those events. It begins with an outline of the press censorship, and it brings to light a surprising failure that allowed the 7 November armistice information to be circulated throughout the country. Clear evidence of this failure seems to have been left undisturbed in the Home Office archives since 1918.

The Official Press Bureau, housed within the Royal United Service Institution building in Whitehall (RUSI - now the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies), was set up at the outset of the First World War under War Office supervision. In June 1915, soon after the formation of Herbert Asquith’s coalition government, overall responsibility for it was transferred to the Home Office, and its day-to-day control entrusted to two co-directors: Sir Edward Cook (picture), a renowned author and former journalist, and Sir Frank Swettenham, a distinguished former colonial administrator in Malaya, both of whom had been assisting the previous director “in an honorary capacity”. They remained co-directors until the Bureau closed at the end of April 1919.

As a historical record, Sir Edward wrote an account of the Press Bureau’s work which he and Sir Frank felt had been widely misjudged throughout the war. “Certain it is,” he remarked, that “no one outside the Office, not even the Press, ever really understood the Press Censorship, or what had to be done and was done at the Official Press Bureau.”

The outline here is based mostly on Sir Edward’s retrospective, completed not long before he died, and which he called his “essay”: The Press in War-Time, With Some Account of the Official Press Bureau (published in 1920).

The Bureau had three principal functions: to supply the Press with “official news”; to implement a “voluntary” system of newspaper censorship; and to operate a compulsory censorship of newspaper telegrams. The Bureau’s “Issuing Department” had responsibility for the first function; the “Military Room” for the second; and the “Cable Room” for the third function.

The Bureau had three principal functions: to supply the Press with “official news”; to implement a “voluntary” system of newspaper censorship; and to operate a compulsory censorship of newspaper telegrams. The Bureau’s “Issuing Department” had responsibility for the first function; the “Military Room” for the second; and the “Cable Room” for the third function.

Based on communiqués from the Admiralty, the War Office, Britain’s Allies and the contents of intercepted enemy wireless bulletins, the Bureau’s Issuing Department provided “a steady stream of trustworthy information” as Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, described it in August 1914. Its press releases were passed on to the newspapers through a “Press Room”, where journalists were usually “in constant attendance”.

Editors were not required by law to submit information relating to the war to the Press Bureau before publishing it, “whether in the form of articles, photographs or drawings”. Newspaper censorship operated on “a voluntary system”: editors decided themselves whether to have such items scrutinised beforehand by the censors.

In practice, most editors tended to play safe and usually did submit them to the Military Room. There were many wartime regulations prohibiting reporting of a whole range and variety of information bearing in some way on the war, regulations - usually requiring official clarification - which were contained in the Defence of the Realm Act. They carried severe penalties for transgressors.

It was to avoid falling foul of these that editors generally opted for censors’ clearance, a choice which “thus relieved [them] of responsibility”. Perhaps for those who did not appreciate it at the time, the Bureau, Sir Edward pointed out, was “a shield for the Press”.

In the case of information carried in telegrams - “more potentially dangerous than information sent in a less speedy way” - there was no choice for editors, or for anyone else. Censorship of all telegrams - those coming from abroad (“inward”), those going abroad (“outward”), and those staying within Britain (“inland”) - became compulsory right from the start of the war.

The Bureau was responsible for censoring all inward, outward and inland telegrams “of a Press character”, that is, those “addressed to or from a newspaper”. Once separated from the rest, these were sent to the Bureau’s own censors in the Cable Room before being delivered or dispatched. Indeed, censoring press telegrams was “the first function of the Bureau” according to Sir Edward.

As a rule, press and non-press telegrams all passed through the General Post Office’s Central Telegraph Office building (CTO) in London’s Newgate Street. From here, Post Office Telegraph Service (TS) employees diverted inward and outward press telegrams, regardless of content, to the Press Bureau, sending them in cylinders along a small-bore underground pneumatic tube direct to the Bureau’s “Tube Room” in the RUSI building. Here the telegrams were logged, placed in a queue, and then sent up to the Cable Room to be processed.

Not all inland press telegrams, however, were diverted: only those judged to be about the war were sent from the CTO to the Bureau. In Sir Edward’s words, which he does not clarify, the Bureau only received “Inland Press Telegrams as were deemed by the Post Office to be connected with the war. This last class was not numerous, as the Post Office exercised a very reasonable discretion.”

Not all inland press telegrams, however, were diverted: only those judged to be about the war were sent from the CTO to the Bureau. In Sir Edward’s words, which he does not clarify, the Bureau only received “Inland Press Telegrams as were deemed by the Post Office to be connected with the war. This last class was not numerous, as the Post Office exercised a very reasonable discretion.”

Apparently, therefore, the system was that clerks at the CTO separated the press telegrams from the many others arriving in the building at any one time; diverted inward and outward press telegrams to the Press Bureau; and allowed some inland telegrams - the ones not considered to be carrying war information - to go through without being seen by the censors. The non-press telegrams were sent to on-site censor rooms staffed by the War Office.

Sir Edward’s remarks about inland press telegrams and how the Post Office handled them seem ambiguous, paradoxical even, in his book; but in the context of events surrounding the Reuter armistice bulletin of 7 November, they are most pertinent.

Reuters acquired the 7 November armistice information from a contact who knew that the American embassy and military authorities in London - all located in Grosvenor Gardens at that time - had received it from France and believed it to be official. Who the contact was is unknown. Reuters protected his identity by describing him discreetly as “an unofficial, but unimpeachable, channel”. On one occasion they implied that he had obtained the information via the US Navy Headquarters, on another via the Army Headquarters.

Reuters sent the information out during the afternoon of Thursday 7th, but then cancelled it within a matter of minutes. Later that day, a report signed “J.C.” (the initials it seems of a Colonel Clarke, probably an on-site War Office censor at the CTO) reached the Press Bureau outlining what had happened.

It states that at 3:58 pm a telegram from Reuters was sent to the Press Association with the message:

"Reuter’s Agency is informed that according to official American Information the Armistice with Germany was signed at 2.30."

Then, “at 4.15 p.m.” Reuters sent another message - presumably also to the Press Association - urging: “Suppress message of signing armistice.”

During those 17 minutes before its cancellation, the Press Association relayed the information to its mostly provincial newspaper members, while Reuters also sent it to some London newspapers. Almost immediately, these released the false news to the general public: the cancellation message failed to abort it. As the news spread - with remarkable speed - people around Britain left their homes and poured out of workplaces to celebrate.

What happened in London during that interval to induce Reuters to withdraw the bulletin is not known. Possibly, their “channel” between Reuters headquarters at Old Jewry in the City and Grosvenor Gardens warned them that authorities in Paris were now refuting the armistice news. In France, where it was the same time as in Britain in November 1918, official denials were being issued towards late afternoon; one of these could have reached the American Embassy in London by then.

Reuter’s Agency is informed that according to official American Information the Armistice with Germany was signed at 2.30.

During the equivalent 17 minutes in Brest, Roy Howard, the United Press president, was hurriedly preparing to send his armistice message to New York City. Not long after it arrived there and started spreading around the United States, Admiral Wilson, who had given the information to Howard, received a follow-on military wire from Paris denying it. Howard was told not long afterwards, just as he and some acquaintances were about to start celebrating the end of the war.

The same evening in London (the co-directors took it in turns to work at the Press Bureau until midnight) Sir Frank Swettenham reported the “serious matter” of the Reuter armistice bulletin to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) Sir Charles Mathews. Reuters, he wrote, made “no reference to us before circulating [its] statement to the Press”; the statement “is quite untrue, and… has gone all over the country.” The following day, Sir Edward Cook informed the DPP that the Press Association had also sent telegrams “throughout the country” with the same false armistice information and “without any reference here” beforehand.

In a separate communication to the DPP, Sir Frank enclosed a report from the Director of Transports at the Ministry of Shipping detailing “the serious situation created in mining and ship-loading circles at Cardiff yesterday by the circulation of false news [about] the signing of an armistice with Germany”.

The Transports Director complained that, in the wake of the news:

"some of the Dock Labourers and Miners at Cardiff and Newport stopped work, and in some cases have remained out to-day. The effect of this was that about 50,000 tons of coal which would have been available for export was lost for shipment and in view of the serious arrears on all coal programmes due to the general shortage of coal, this loss is to be regretted."

He urged that all possible action be taken in future to prevent “similar premature announcements”.

Judging the Press Bureau’s complaints to be “grave and well founded” the DPP referred the letters to the Attorney-General. Sir Frederick Smith’s response, having given the matter his “serious consideration”, was that both Reuters and the Press Association must be prosecuted.

Neither agency had broken the law by circulating the armistice bulletin without first submitting it for clearance by the Press Bureau censors. This, as Sir Edward Cook reminded Colonel Clarke at the time, was not how the newspaper censorship worked: “The internal censorship is, as you are aware, voluntary and the News Agencies do not always submit to us news for publication in this country.”

Indeed, the co-directors’ statements in their letters to the DPP that Reuters and the Press Association both circulated the news “without any reference here”, rather than implying an offence merely stated a fact and indicated that the Bureau itself had not erroneously approved the armistice message beforehand.

The offence the two agencies committed was one the Press as a whole risked by exercising the right not to submit material for censorship - the criminal offence of violating Defence of the Realm Act regulations - in this instance, Regulation 27 specifying that:

"No person shall by word of mouth or in writing or in any newspaper, periodical, book, circular, or other printed publication - (a) spread false reports or make false statements…"

Applying “common sense”, the Press Bureau’s usual practice was to overlook Regulation 27 transgressions, except, Sir Edward noted, where false statements were “clearly and beyond the reach of disputation false, and… of real consequence”. Reuters’ and the Press Association’s transgressions of 7 November 1918 glaringly fulfilled the criteria for exceptional legal action.

Thus, for having distributed the armistice scoop, SC Clements for Reuters, and general manager HC Robbins for the Press Association, now found themselves in serious breach of the law. They faced penalties of imprisonment “with or without hard labour for six months”, a £100 fine, “or both”, plus possible seizure of their “newspaper plant”.

At Reuters, Clements must have moved quickly to get the armistice message out to subscribers. As he probably saw it, the news could break and become generally known at any moment, robbing the agency of its exclusive. To play safe and submit it to the Press Bureau’s inevitable delays was too much of a risk.

In any case, it came as “official American Information” and just a few hours after what he described as “positive statements” in some newspapers that the German armistice delegation had already crossed the front lines. Clements regarded these reports as further indication that the message now received about the armistice signing must be true.

The Lobby correspondent of the London Daily News had indeed reported rumours in Parliament that the German delegates crossed the British lines late on Wednesday night - 6 November - and that they were due to meet Marshal Foch on Thursday. Some morning papers published short items offering different versions of these rumours alongside other items based on German newspaper announcements about their armistice delegation. They were hardly “positive statements” - more a mixture of confused information and speculation about an armistice - sooner rather than later - with Germany. But at the time they certainly lent credibility to the false armistice news itself. Not only Clements would have been encouraged by them.

On balance, therefore, from his perspective there were probably few, if any, convincing reasons not to circulate the armistice news straight away.

How the Reuter and Press Association people felt and what they thought when they were told, only minutes after sending out their bulletins, that there was no armistice after all, can only be imagined. In similar circumstances in Brest, United Press president Roy Howard, his face “white [and] drawn” as he “realized what he had done”, gradually underwent “a revival of hope”, the American Army Base’s intelligence officer Arthur Hornblow, later recalled. Unwilling to accept that not a word of the message he had sent to New York City was true, Howard became convinced that - for some reason - official confirmation was being held up, and spent “most of the night” waiting for verification from his Paris office. At Reuters and the Press Association they obviously reacted quickly following the initial shock - trying within minutes to stop the bulletins reaching the public. Their rapid responses - albeit unsuccessful - earned them credit later from the Attorney-General.

How the Reuter and Press Association people felt and what they thought when they were told, only minutes after sending out their bulletins, that there was no armistice after all, can only be imagined. In similar circumstances in Brest, United Press president Roy Howard, his face “white [and] drawn” as he “realized what he had done”, gradually underwent “a revival of hope”, the American Army Base’s intelligence officer Arthur Hornblow, later recalled. Unwilling to accept that not a word of the message he had sent to New York City was true, Howard became convinced that - for some reason - official confirmation was being held up, and spent “most of the night” waiting for verification from his Paris office. At Reuters and the Press Association they obviously reacted quickly following the initial shock - trying within minutes to stop the bulletins reaching the public. Their rapid responses - albeit unsuccessful - earned them credit later from the Attorney-General.

Sir Frederick Smith demanded explanations from both agencies for their distribution of false reports about the war. He rejected Reuters’ plea (made by SC Clements presumably) that they had acted on information, reaching them “through” American Army Headquarters, “which they had understood to be official”. And he dismissed the Press Association’s excuse (given by HC Robbins presumably) that they had never known Reuters - their “source” - to have been “unreliable in any information they had previously supplied”. With regard in particular to the “disastrous and irremediable result” of the armistice reports, as detailed in the Ministry of Shipping’s complaint to the Press Bureau, “neither of these so-called explanations was considered satisfactory”.

Nevertheless, after “not only [a] careful but [also] anxious consideration” Sir Frederick decided against prosecution, and instructed Sir Charles Mathews to inform the Press Bureau’s co-directors of his reasons. The DPP’s letter is dated 19 November 1918, 12 days after the false armistice bulletin went out and a week after the war ended.

There were mitigating circumstances. Firstly, Reuters and the Press Association had “with all possible speed” cancelled the armistice report. Secondly, as the Armistice was signed only a few days later, it was unlikely that “any Court would take a serious view of, or impose any substantial penalty” for the armistice report on 7 November. Thirdly, a prosecution of the two agencies could not provide “any compensation” or remedy for the adverse economic effects of the false news, such as the “grave and even disastrous” loss of coal exports from South Wales.

There had also been representations from influential quarters. For while the Attorney-General was considering the case, “more than one Government Department” had “approached” him praising Reuters for its “long, valuable, and patriotic service… to the country… during the four years of the War”. The Foreign Office in particular had spoken to him of what it called the agency’s “inestimable usefulness”.

By implication, Sir Frederick was favourably impressed by these approaches; allusions, it seems, to confidential wartime arrangements organised by Reuters’ managing director Roderick Jones. In his 1999 history of Reuters, Donald Read characterises these arrangements as placing the agency’s “reputation as well as its network at the service of the British Government”, for what were essentially propaganda purposes.

Sir Frederick could also have pointed out that if the case had gone to court, the evidence - heard in public - might well have proved embarrassing for Britain’s American allies at their embassy and military headquarters in London. An additional consideration it seems unlikely he would have overlooked during his deliberations.

On the Attorney-General’s instructions, the DPP wrote “stern and peremptory letters” to Reuters and the Press Association, in which he dwelt upon the “enormity of their offence” and of “its misleading and costly result” that “could have been avoided” had they referred to the Press Bureau. He made clear to both “how narrowly they had escaped a well merited punishment”.

No doubt to their great relief, the two agencies thus emerged from many days of uncertainty with strongly-worded official reprimands for their parts in bringing the False Armistice to Britain.

Perhaps because the statement had come from Reuters - well known, highly regarded, and prestigious - and was clearly marked “official American Information" the clerks decided not to hold up the nation’s longed-for good news by sending it to the Press Bureau

There is, however, a remarkable aspect of this story that the Press Bureau directors appear not to have disclosed to the DPP and Attorney-General, or if they did, did so unofficially and without record. An aspect that any court proceedings against Reuters and the Press Association might well have exposed.

This is the fact that on 7 November 1918 Post Office clerks and telegraphists at the CTO allowed the Reuter armistice bulletin to be sent out as an inland press telegram without first diverting it to the Press Bureau’s Cable Room censors. Sir Edward excludes this information from his book. But his remarks there about what he calls the Post Office’s “discretion” over inland press telegrams are perhaps an oblique, critical reference to it.

As Sir Edward pointed out, Post Office CTO employees diverted to the Press Bureau inland press telegrams “as were deemed by [them] to be connected with the war”.

The Reuter armistice message was obviously “connected with the war” - it could hardly have been considered otherwise - and so should have been sent to the censors. But when the CTO clerks saw it, instead of diverting it they “deemed [it] important” enough to be “given priority” for immediate transmission - “with the result that it was signalled pretty well everywhere” within a very short space of time. “What I don’t know,” Colonel Clarke confessed in his report to the Press Bureau, “is why T.S. should have accepted Reuter’s statement without submitting to you or me.”

Their reasons remain unexplained. Perhaps because the statement had come from Reuters - well known, highly regarded, and prestigious - and was clearly marked “official American Information”, the clerks decided not to hold up the nation’s longed-for good news by sending it to the Press Bureau. Or perhaps they simply misunderstand the procedure for dealing with inland press telegrams.

The clerks did send armistice telegrams to the censors on 7 November - large numbers of them that “flooded” in throughout the evening. These, “containing the same information” as the Reuter and Press Association bulletins, were, however, private messages to destinations “outside this country” informing others of the good news that had reached Britain. As outward telegrams, the CTO clerks dutifully sent them not only to the Press Bureau censors but also to the War Office censors in the CTO building, who together blocked them all.

At least, the false armistice news of 7 November 1918 seems to have been prevented from spreading to any other countries, inside or outside the Empire, from Britain.

With Reuters and the Press Association reported to the DPP, Sir Edward reprimanded the Post Office. The “C.T.O.,” he affirmed, “should enquire of us before passing any such announcement as the one circulated by Reuter and the Press Association yesterday afternoon.” And reiterated, “We think it would have been well if the Post Office had made enquiries here before passing the [armistice] messages for inland circulation.” The Post Office Secretary immediately instructed the CTO not to distribute without confirmation “any announcement regarding an armistice” not coming from the Press Bureau.

A week later, Sir Edward wrote to them again: a curt note stating that because of the “cessation of hostilities” they were now no longer required “to divert any Inland Press Telegrams to this office for censorship”.

The clear implication from the Home Office records is that Reuters and the Press Association were admonished for spreading false information about the war that the CTO ought not to have released in the first place. Had TS clerks diverted the Reuter bulletin to the Press Bureau’s Cable Room, the censors there would undoubtedly have stopped it. The Press Association would not have sent its telegrams to newspapers around the country. And Britain would have been spared the False Armistice and all it entailed there.

It seems that the part CTO clerks played in the false armistice events of 7 November 1918 has remained unreported for nearly a century. But their immediate transmission of the uncensored Reuter armistice bulletin was crucial to the spread of the False Armistice to Britain. As crucial as the absence of the French censors from the telegraph building in Brest was in allowing false armistice news to leave France in Roy Howard’s cablegram. And as crucial as the decision of the American censors in New York City to wave through that cablegram was in opening the United States to the False Armistice, and all the other countries it spread to from there.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 48 of 49