Columns

A tale of three barons and the empire they built

Tuesday 6 February 2018

Most acquisitions fail. Two out of three M&A transactions do not achieve the promise of financial and strategic expectations. Reasons range from inadequate planning to lacklustre execution to conflicting cultures - adjusting to “the way we do things here”.

Multiple case studies by business schools show the poor performance of acquisitions to be a fact of corporate life. The lesson does not stop titans of industry from trying to beat the odds. Growing a business by acquisition rather than organically is still thought to be the best way to become big quickly.

The Thomson family, Canada’s richest with a fortune now reckoned at about $22 billion, must have thought about the M&A hit rate when it acquired Reuters ten years ago. The head of the family, David Thomson, is one of the world’s wealthiest people and known to be intensely private so his thinking at the time may never be disclosed.

What is known is that the reduced Thomson Reuters that emerges from the group’s biggest shake-up since the takeover - the sale of a majority of its core business with lucrative recurring revenues - is seen as returning the Thomsons to their roots.

News has been close to the hearts of three generations of Thomsons.

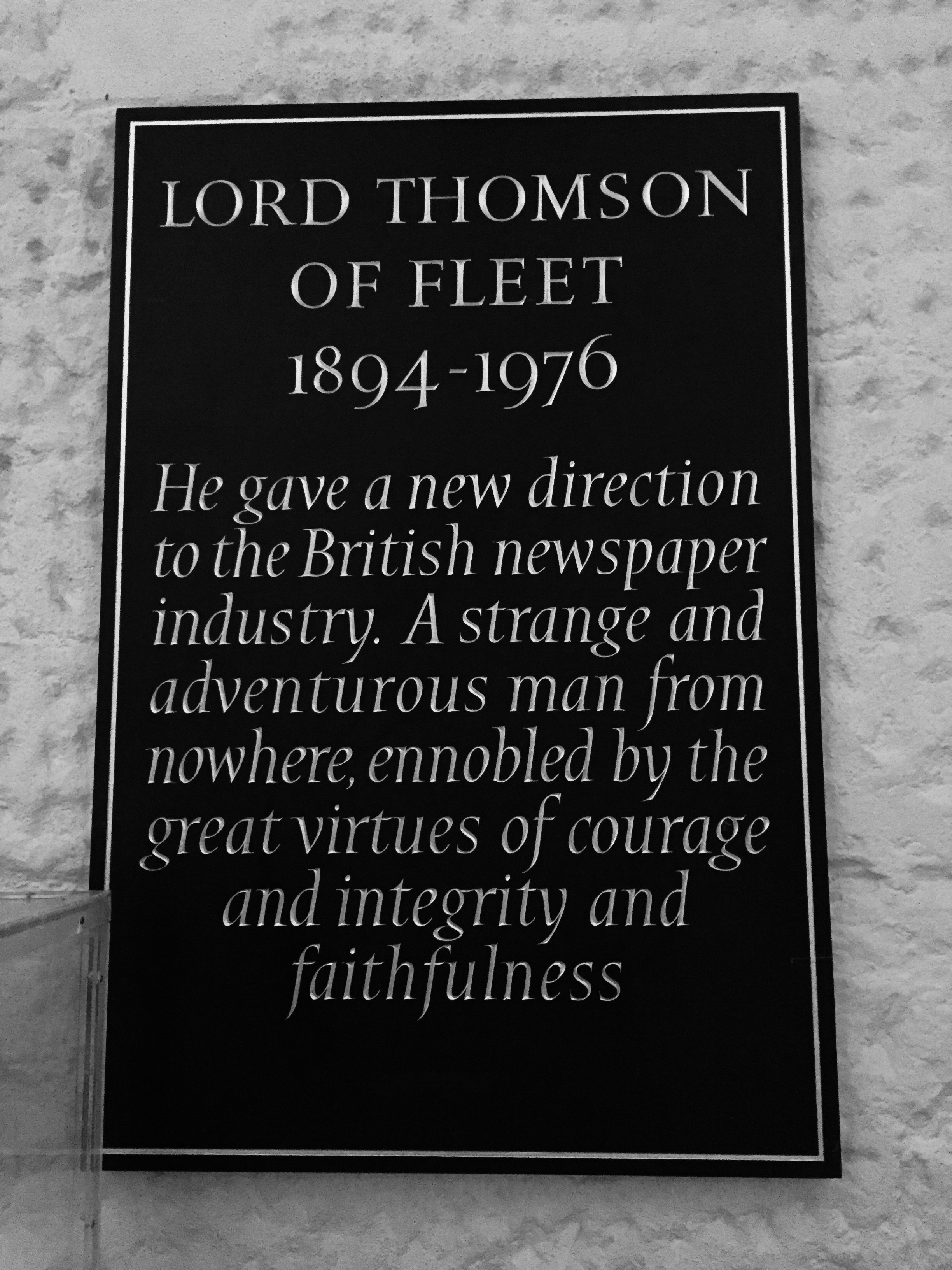

Roy Thomson (1894-1976) - “A strange and adventurous man from nowhere” as his memorial tablet in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, records - was a Depression-era radio salesman reputed to be descended from a small Scottish clan of 15th century border raiders. He launched his own radio station in 1931 and three years later, as publisher of a small town newspaper in Ontario, founded the Thomson Corporation.

Roy Thomson (1894-1976) - “A strange and adventurous man from nowhere” as his memorial tablet in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, records - was a Depression-era radio salesman reputed to be descended from a small Scottish clan of 15th century border raiders. He launched his own radio station in 1931 and three years later, as publisher of a small town newspaper in Ontario, founded the Thomson Corporation.

Over the next four decades Thomson built a diversified transatlantic empire comprising newspapers in North America and the United Kingdom, a Scottish television channel, a British airline, an international travel agency and North Sea oil exploration.

Commercial television in Britain in the 1960s was so profitable it was “like having your own licence to print money,” he famously said.

Roy Thomson’s success was rewarded with ennoblement as Baron Thomson of Fleet, an hereditary British peerage that, under Canadian law at the time, required him to surrender his citizenship.

The title passed to his son Kenneth (1923-2006), who added book publishing, legal and scientific businesses and more newspapers to the empire and sold others, as well as the North Sea oil holdings. The disposals included The Times to Rupert Murdoch and the Jerusalem Post to Conrad Black.

Roy Thomson’s grandson David, now 60, is the third baron and current chairman of the family business. Like his father before him, he has not taken up his seat in the House of Lords.

Also like his father, he is an avid art collector, owning the world’s largest collection of works by John Constable. The entire collection has included some monumental purchases by both father and son. Peter Paul Rubens’ The Massacre of the Innocents was bought by Kenneth and David Thomson for a world record auction price of $49.5 million in 2002 and subsequently donated to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto where it hangs as its most illustrious centrepiece.

The dynasty’s founder made certain that the wealth he had amassed remained in family hands after he was gone.

“David, my grandson, will have to take his part in the running of the Organisation and David’s son, too,” he wrote in his 1975 autobiography. “With the fortune that we will leave to them go also responsibilities. These Thomson boys that come after Ken are not going to be able, even if they want to, to shrug off these responsibilities.”

Three decades after his death, the Thomson Corporation under the leadership of the founder’s grandson acquired its biggest trophy, Reuters, and became Thomson Reuters with a 55 per cent financial interest for the family’s investment holding company Woodbridge. That stake is now 64 per cent.

The takeover extended the Thomsons’ reach into new areas of financial services and new parts of the world, while the news agency added lustre to the Thomson brand and gave it global recognition and clout.

The conglomerate’s first annual report recorded 2008 as “a milestone year in which we completed our acquisition of Reuters for approximately $17 billion. As a result, we became a much larger and more global company”.

At the takeover, the group employed more than 50,000 people in 93 countries. The following year the number rose to 55,000 and peaked at 60,500 in 2011.

Despite the global financial crisis, Thomson Reuters finances grew with three years of better than expected cost savings following the merger. It struggled to integrate the two companies’ legacy products, however.

TRI stock fell during the crisis and when the shares recovered they did so at a slower rate than that of the broader US equity market.

Cost cuts and divestitures made the organisation slimmer. First the healthcare information business was sold, then intellectual property and science. Waves of redundancies and employee contract buyouts reduced the payroll and removed costs from the balance sheet.

The future of Reuters takes precedence over the principles

Thomson Reuters invested billions in share buy-backs rather than using its cash to develop new products, seen as an indication management had run out of ideas.

Ten years after the takeover - a decade in which more than 200 companies were acquired - the worldwide headcount of about 45,000 is about to be halved as the combined business is dismembered.

Some 22,000 or so employees will transfer from Thomson Reuters to a new partnership with Blackstone, the world’s biggest private equity firm, which is buying 55 per cent of the group’s largest unit, financial and risk.

Staff moving to the new employer include about 16,000 people in F&R and 6,000 others across corporate functions to support the new entity.

Joining Blackstone as junior partners in the venture are two of its clients, Canada’s largest pension fund and a Singaporean sovereign wealth fund.

The business they are taking on has 440,000 financial data users spread across the world's biggest investment banks, private equity firms and hedge funds.

Thomson Reuters is keeping exclusive control of Reuters News, the agency founded by Paul Julius Reuter in 1851. Reuters, with 2,500 journalists around the world, will receive an annuity of at least $325 million a year for 30 years, adjusted for inflation, from the new Blackstone-led F&R firm in return for the right to use news supplied by Reuters on its terminals. The new business will be Reuters’ largest client, as F&R is now.

Reuters News, part of Thomson Reuters’ loss-making corporate unit, accounts for three per cent of overall group revenue.

Historically, no single individual could own more than 15 per cent of Reuters. The first of the five Reuters Trust Principles drafted in 1941 to protect the organisation from government or other outside interference, amended slightly in 1984 when the company floated on the London and New York stock exchanges, states: "Reuters shall at no time pass into the hands of any one interest, group or faction.”

When it bought Reuters the Thomson family was allowed to ignore that prohibition, despite worries that a single majority shareholder would sully Reuters' reputation for unbiased journalism.

Pehr Gyllenhammar, a Swedish industrialist, was chairman of the Reuters Founders Share Company which acted as guardian of the Trust Principles. He justified the waiver on the ground of Reuters’ poor financial circumstances at the time.

"The future of Reuters takes precedence over the principles,” he declared. “If Reuters were not strong enough to continue on its own, the principles would have no meaning.”

The Thomson family agreed to vote as directed by the Founders Share Company on any matter its trustees might deem to threaten the Principles. Woodbridge would be allowed exemption from the first principle as long as the investment holding company remained under Thomson family control. The Principles were adopted as a code for conducting business across the new corporation.

Now, with the disposal of a controlling interest in the “old Reuters” terminals and data business, the Principles are to be subject to “consequential modifications” to ease completion of the deal in the second half of this year.

Ten years ago, Reuters dominated the financial information sector. Thomson Reuters failed to keep up with the relentless advance of its most aggressive competitor Bloomberg, which overtook it to become the market leader with a share in 2016 calculated at 33.4 per cent, compared with Thomson Reuters’ 23.1 per cent. A decade earlier those positions had been reversed, with Reuters dominant.

In leveraged buyouts, there’s always an exit strategy. Blackstone’s for profiting from its investment - sale or spin-off in an IPO when the business has improved - remains to be seen.

It is known for cost cutting to extract maximum value from its investments. Expect that to occur in the F&R business to make it leaner and fitter for eventual sale or flotation.

PHOTO: “A strange and adventurous man from nowhere” - Roy Thomson’s memorial plaque in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 8 of 65