Comment

Double agent in Warsaw

Tuesday 13 February 2018

Many us who worked in Warsaw in the Soviet era will have affectionate memories of Karol Cwinarowicz. He was a hard-working, very likeable but rather bumbling local journalist, and from 1963-85 he loyally served a succession of nine Reuter correspondents. He was also a double agent.

Many us who worked in Warsaw in the Soviet era will have affectionate memories of Karol Cwinarowicz. He was a hard-working, very likeable but rather bumbling local journalist, and from 1963-85 he loyally served a succession of nine Reuter correspondents. He was also a double agent.

I worked with Karol throughout the momentous first phase of the Solidarity Revolution from 1979 to 1982 and during our long hours together I pieced together a fair amount about his extremely tough life. Born in the then Polish city of Lwów in 1922 in what is now Lviv in Ukraine, Karol witnessed as a young man the triple blows in WWII of two Soviet invasions and German occupation, and the extermination of the local Jewish population under the Nazis. When the Soviets took over again after the war, he underwent forced repatriation to Poland. He settled in Warsaw, and at some stage in the late 1950s or early 1960s he made a journey to England where he was recruited as an agent for the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), otherwise known as MI6.

Almost immediately on returning to Warsaw from this fateful trip, Karol was arrested and put on trial accused of espionage and sentenced to jail. He had been betrayed. This much I learned from him. He had talked to me about his trial and imprisonment in Warsaw’s infamous Mokotów Prison, and about how it had come about because he had been in touch with certain opposition people when he was in England (he was understandably vague about this). In characteristic Karol fashion (because of his asthma he had a twitch and slight stutter, and it was often difficult to get him to be clear-cut) he told me that at his trial he had pleaded both guilty and not guilty. I recall vivid details of his account of prison life - the lights, for example, coming on for a few minutes every hour throughout the night.

Many years later I picked up the trail of Karol’s double life. I went back to Poland in 2014 to donate to the new Solidarity Museum in Gdańsk a suitcase of stories I had written during the Solidarity Revolution and reams of press cuttings and other material, such as posters and leaflets, from that turbulent period. Return to the Gdańsk shipyards, the birthplace of Solidarity, and a subsequent talk I gave there, re-kindled my interest in my time in Poland, and I applied to see my Polish SB (secret police) files.

The files are not remarkable - more Marx Brothers than Karl Marx - and the reporting on me was mostly second-rate. But there was one consistent source (referred to by the tag TW, the Polish initials for secret collaborator, with the code of JKM and with one telling reference as being “from Reuter”) who informed on me regularly. I was curious to find out who he was, and applied for and obtained at least some of this TW’s files. The source turned out to be - unsurprisingly - Karol Cwinarowicz. While in prison, he had been turned by the SB; he was released after serving just two years on condition that he collaborated with them. It would have been naive not to have suspected anyone working for a Western news agency under Communist rule to have co-operated with their country’s secret police; almost certainly Karol also informed on my predecessors and successors.

Karol’s information about me, and most probably also about other Reuter correspondents, was quite harmless. But his file contained an astonishing story about what followed many years later. He was given an assignment to contact British intelligence through the British Embassy in Rome while on holiday there in 1981 and instructed to demand back pay and compensation for being betrayed and imprisoned.

The SB file describes - in Karol’s own words - all the details of his dealings with the British embassy in Rome in June that year. His mission was to note and report on everything he saw and on everyone he met. He even describes the body scanner used on him at the embassy entrance.

After a series of secretive encounters, Karol was taken in hand by an SIS agent who subsequently met him at his hotel and took him for a de-briefing to a nearby café.

“I described my arrest and the further consequences I had endured as a result,” Karol wrote. “I requested compensation and said I was counting on an affirmative settlement of my requests. In the present situation a sum of around $20,000 should not be an exaggeration.”

“(The British agent) said he had checked my name which is on the British intelligence list and intelligence is extremely sorry about my unmasking and trial… (British) intelligence never forgot those who have done something for them.”

“I also told him I was surprised at being arrested so quickly. He replied that such things do happen, adding that the British authorities were very sorry for that.”

In the end Karol was offered only £3,000.

“When I subtly hinted that his was a non-too-high sum, he replied he had received such instructions from London and that the main issue is how to relay the sum.”

The Warsaw embassy was deemed too risky, so it was arranged for Karol to collect his payment in cash at the British Embassy in Vienna.

I remember that trip. Karol was increasingly anxious in the days before lest a crisis keep him grounded in the Warsaw bureau. But he did get to Vienna in September 1981, and he came back with some smart new clothes. I understand now how he afforded them.

I had started paying both Karol and our other office assistant Wiktor Zdunek in US dollars, rather than in near worthless Polish złoty, and that made life significantly better for them. But looking back, I don’t think Reuters did enough for the plucky few who crossed the line and came to work for us in our Eastern European bureaux during the Cold War. Did the company provide them with pensions? I hope Karol’s Polish minder, Major A Sobczyński, allowed him to keep all of his back pay. He certainly deserved it.

Karol retired in 1985 and died in Warsaw in December 1988 less than a year before the end of Communist rule in Poland.

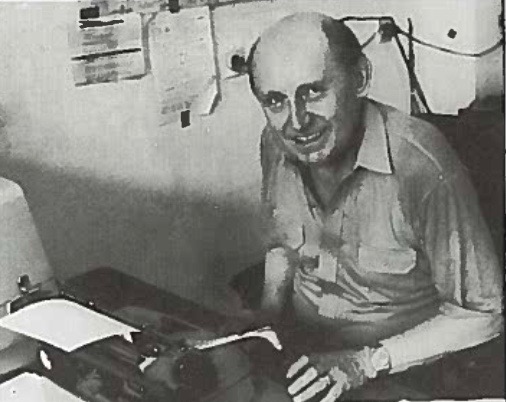

PHOTO: Karol Cwinarowicz in the Warsaw bureau. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 656 of 1808