Library

Hubert from Hull: erudite, unregenerate, agreeably raffish

HUBERT NICHOLSON - Little Heyday - Heinemann - 1954

“How many First World War books can the nation bear?” The Times Literary Supplement cried in near exasperation as works occasioned by the centenary of the 1914-18 conflict poured into its bins, hungry for review. As I took stock of the TLS outburst, I happened to be combing through an assortment of miscellaneous volumes from my own shelves unread in many years. I came on one that obliquely touched on the “Great War” and, moreover, claimed a former and flamboyant Reuterian as its author.

“How many First World War books can the nation bear?” The Times Literary Supplement cried in near exasperation as works occasioned by the centenary of the 1914-18 conflict poured into its bins, hungry for review. As I took stock of the TLS outburst, I happened to be combing through an assortment of miscellaneous volumes from my own shelves unread in many years. I came on one that obliquely touched on the “Great War” and, moreover, claimed a former and flamboyant Reuterian as its author.

It was the 1988 paperback edition of a novel first published 60 years ago. It bore the deceptively playful title of Little Heyday and was set in a rural stretch of the native East Yorkshire of its creator, Hubert Nicholson (1908-1996). Little Heyday concerned one day in the life of an eight-year-old farm-loving boy named Dicky and the flash-backed history of his agrarian family. Quickly I was drawn into a re-read and discovered again the author’s unerring eye for the child’s perspective and the rural world of England in the early 20th century.

What gives the book its Great War aspect is the fact that the single day at issue happens to be 28 June 1914, the day - unbeknown, of course, to the contemporary country-folk of the East Riding - death by assassination came to the heir apparent of the Hapsburg throne in far-away Bosnia. Nicholson’s narrative deftly notes this coincidence early and late in its course and we realise as the book ends that the pastoral life of East Yorkshire faces a war-worked social transformation.

Little Heyday originally appeared nine years into the author’s 23-year sub-editor’s stint at Reuters, Fleet Street. It is a shrewd, vivid and moving evocation of a superseded world. More tempestuous - indeed, horrific at times - was another Nicholson novel that emerged from my pile of neglected books. This was Sunk Island whose initial publication in 1956 followed that of Little Heyday by two years and still represents. I discovered, a peak achievement among the writer’s dozen books of fiction. Back I plunged into the story of compulsive, all-consuming love and of farmland struggle against the grim elements that beset an island region bordering the author’s Hull City birthplace.

The Observer newspaper called Sunk Island a “minor masterpiece” but I would drop the reviewer’s condescending qualifier and single out the book as a leading candidate for prestige-paperback revival. Reason enough for this is Nicholson’s accomplishment in plumbing the primal depths of sexual passion without the preachiness of a writer still vastly influential in the Fifties, DH Lawrence. Nicholson’s succinctness saved him from that.

Frost sharpened the air and Fleet Street, the open-air parlour, sparkled like tinsel. The crowded milk-bar was red with the glow of tomato soup. Pub doors swung continually, letting in more and more thirsty men, letting out orange-coloured gusts of smoke which smelt of brandy.

He was a serious and highly productive poet as well and one is left baffled about where this busy literary man also found the time and energy for Reuter shift work and a crowded social life as an archetypal Fleet Street persona, plus separate whirlwind commitments back on the domestic front. He joined Reuters in 1945 after a newspaper career candidly recalled in his rousing 1941 autobiography, Half My Days and Nights. The subs he encountered at one paper in the Thirties “were tame men, even the choleric sort who filled themselves with beer and then yelled at the editor. But the reporters seemed to me a gang of Elizabethan pirates at the very least. They worked odd hours, they never went home, they had wild parties, they came drunk to the office.”

After his Reuter retirement in 1968, Hubert the poet spared a satiric moment to lament an imaginary “Old Hack”:

He once was fleet as the hidden Fleet

But now he drags his laggard feet

Far from the press of the paper street

With only one deadline still to meet.

There was an impish quality to Hubert’s demeanour and bearded visage, and his electric wit generated, among his fictional works, a cutting 1960 tale called Mr Hill and Friends. I possess only a proof copy of this crackling satirical period-piece (1950s, really, right down to the loud espresso soirées and seedy “milk-bars”), and scrawled in pencil on the brown paper cover is the signature of some now-lost Reuterian. The narrative is partly set in pre-Murdoch Fleet Street and pubs familiar to Reuter toilers long turned “laggard”.

The Old Bell is there, and the Cogers, together with the Falstaff (later Mrs Moon’s) and pub patrons identifiable as AWOL Reuter deskmen of the 1950s. Chapter 19 begins with a classic tableau of a winter evening in vintage EC4:

Frost sharpened the air and Fleet Street, the open-air parlour, sparkled like tinsel. The crowded milk-bar was red with the glow of tomato soup. Pub doors swung continually, letting in more and more thirsty men, letting out orange-coloured gusts of smoke which smelt of brandy. Printers in denims, impervious to the cold, argued on the corners or squatted on their heels in groups, watchful, like Jacobins awaiting their hour, but murmuring only of racing results and waiting for the second edition time. In the Cogers, their feet in the footprints of Johnson and Garrick, Tass men talked to Tanjug and Reuters to Reveillé. The hubbub made privacy possible, as only the nearest speaker could be heard by each person.

How distant Mr Hill and Friends - the sardonic story of a quintessential London con-man - is from the poignant Little Heyday and the haunting Sunk Island! - proof of Nicholson’s broad life-experience and versatility.

Anecdotes abounded about his Fourth Floor exploits. One concerned the writer Henry Miller’s fabled friend, Alfred Perlès. He was given to wide international wanderings, apparently supporting himself with odd jobs under pseudonyms along the way. Hubert was working a News Desk shift one day and called for a messenger to perform a routine service. An aged aide duly turned up and senior sub Nicholson handed him a document for cross-room delivery. Then, astonished, Nicholson did a double-take. “Why, you’re Fred Perlès!” shouted Hubert, who knew all about the raucous Miller entourage. Sheepishly, Perlès confessed his real identity and Nicholson at once ordered the interloper to accompany him downstairs to the Cogers for a welcoming libation.

Nicholson’s father was a “master printer” in Hull, reputed to have learned Spanish in order to read Don Quixote in the original (and/or Italian for Dante’s Divine Comedy). “I stay earth-smitten, blinded in your light,” Hubert the poet wrote in tribute after witnessing the death of the autodidact parent who, with his wife, had assiduously nurtured their son in the literary classics. According to the author Philip Oakes, the senior Nicholson urged his offspring to attend university. “But he refused in favour of what he called the real world and became a journalist” Oakes wrote in a Guardian obituary of Nicholson Jr.

I met the erudite and unregenerate Yorkshire word-man only after his 1968 superannuation from Reuters. By that time his beard and anarchic hair, which had emphasised the mischievous side of his character, were turning a silvery white and his whole bearing took on a rather benign quality, but agreeably raffish.

After joining Reuters in 1974, I began attending sessions of the Epsom Poetry Group, a legendary verse-declaiming circle of which Nicholson had been the founding father in 1950. No abstract explanations or discussions were allowed at the Group’s wholly informal, wine-enhanced gatherings - just the intoned poetry. The sessions were held at various homes in the London suburb. Among these was the handsome house of the late Ron Sly, a close Nicholson friend and long a pillar of the Reuter World Desk after Hubert’s subbing days were over. It was through Ron, immensely literate and possessor of a fine, ex-actor’s reading voice, that I was given access to the Epsom performances in a declamatory role.

Some star poets came to read in Epsom down the years but the meetings became widely known as a pioneer outlet for ordinary verse-lovers to hold forth with the words of bards ancient and modern. After Nicholson died in 1996 aged 87, The Times wrote of the Epsom enterprise he inspired 46 years previously: “Poetry was then still regarded as something to be read silently at home, but the society’s convivial evenings changed that for many people.”

As for opposing generalised debates about the Epsom poems, Nicholson himself - the man who chose “real life” over universities - argued that there were no easy substitutes for the actual experience of listening to the verse:

Let me admit to a long-standing and unprovable belief that poetry is no luxury but a necessity; that without it people suffer malnutrition unawares; and that when they get the vitamin they actively like it - especially so when the poetry… is read aloud.

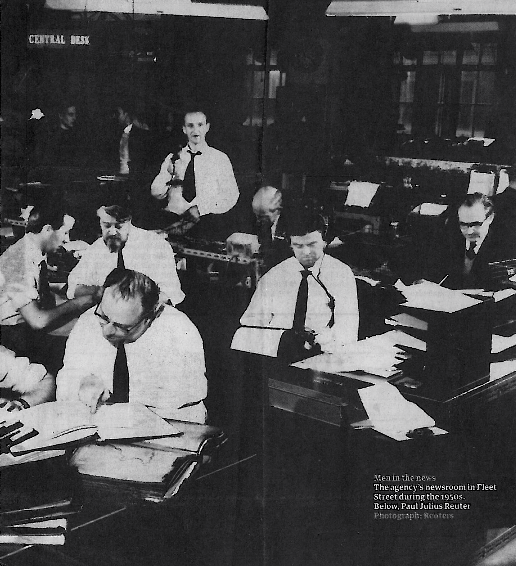

PHOTO: Reuters Central Desk, precursor of World Desk, at 85 Fleet Street in the 1950s. Hubert Nicholson is the bearded figure at left of centre. Standing behind him, Ron Cooper. Far right, Jack Henry.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 21 of 22