People

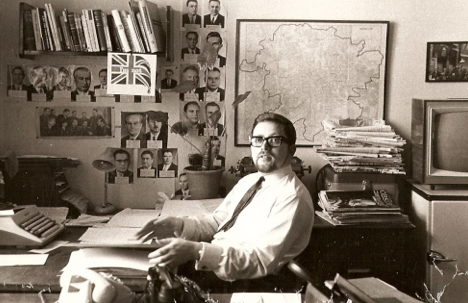

Bob Evans recalls Soviet 'black' envy at US moon landing

Sunday 4 October 2009

In 1969, I was a Reuters correspondent in Moscow when the Americans landed on the moon. With no satellite TV or Internet at the time, the only source of immediate news from the outside world that we - like our colleagues at the other international news agencies AP, AFP and UPI - had was our own news service coming in on an ancient teleprinter in the cockroach-ridden kitchen of our office. As Soviet cosmonaut Georgy Grechko recalled recently, Soviet radio and TV ignored the event and provided no live coverage.

In 1969, I was a Reuters correspondent in Moscow when the Americans landed on the moon. With no satellite TV or Internet at the time, the only source of immediate news from the outside world that we - like our colleagues at the other international news agencies AP, AFP and UPI - had was our own news service coming in on an ancient teleprinter in the cockroach-ridden kitchen of our office. As Soviet cosmonaut Georgy Grechko recalled recently, Soviet radio and TV ignored the event and provided no live coverage.

As the lunar module touchdown was about to begin, and with other "capitalist" journalists living in our foreigners ghetto joining us, we and our wives were crowded around the ancient Siemens watching the story from our Reuter colleagues in the US tapping out at 75 words a minute. With about five minutes to go before landing, the printer suddenly coughed and went dead. Colleagues at the other agencies confirmed that their printers had also gone silent. The BBC World Service, always difficult to pick up in Moscow on short wave, was impossible to hear at that time of night, and it was probably being jammed anyway.

Then, with the drama over, 15 minutes later the four news agency printers in different parts of Moscow started up again.

Next morning I called the Ministry of Communications, officially the provider of the line although we knew that other branches of the Soviet administration had more interest in supervising what was coming in on it. The response: it was a technical problem.

It was only 20 years later, when I was back in Moscow for Reuters during Gorbachev's glasnost period, that a friend in the Soviet news agency TASS confirmed that the order for the cut-off had come from the Communist Party's Propaganda Department. It was far from obvious just what this was meant to achieve, apart from giving a large group of foreign correspondents and their families in Moscow more reason to dislike a system whose officials could be so petty. However, it was not just officials who showed a deal of pettiness. Soviet journalists themselves had for days been bitter about the prospects for the landing, some even suggesting it was bound to fail. Grechko said in a BBC interview marking the 40th anniversary of the landing this July that the Soviet space team, of which he was just a junior member at the time, felt "white" rather than "black" envy for the American triumph. That may well have been the case among space professionals. But among the Soviet media people and Foreign Ministry officials with whom we had to deal, the mood was certainly "black".

"You think you're so all-powerful," one commentator for a Soviet newspaper said to me bitterly at the time (suggesting that he saw the moon landing as a triumph not only for the US but for the West as a whole). "But just wait and see. We'll show you." ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 546 of 575