Archives

Sir Roderick Jones's finest hour

Sir Roderick Jones, managing director of Reuters from 1916 to 1941, was not universally popular. Imperious and autocratic, his image was far from everyone’s cup of tea, and as the years went by increasingly won him enemies. From a lower-middle class background (about which he never spoke), he was the sort of man who in his own memoirs mentions by name everyone who mattered. In the memoirs of most other people his own name is noticeably absent.

Sir Roderick Jones, managing director of Reuters from 1916 to 1941, was not universally popular. Imperious and autocratic, his image was far from everyone’s cup of tea, and as the years went by increasingly won him enemies. From a lower-middle class background (about which he never spoke), he was the sort of man who in his own memoirs mentions by name everyone who mattered. In the memoirs of most other people his own name is noticeably absent.

What most people would not dispute however is that Jones recognised reputation and success when he encountered it. With this in mind, it is unsurprising that, for him, by the twenties, The Savoy, one of London’s most elegant and fashionable hotels, had become very much a second home.

The hotel was conveniently located. From Reuters Head Office at 85 Fleet Street, it was but a short walk or chauffeur-driven car journey along Fleet Street and the Strand to its main entrance. Between the wars, it boasted two resident dance bands - the Savoy Havana Band and the even more famous Savoy Orpheans, led by Carroll Gibbons. Wireless broadcasting directly from the hotel via the new BBC meant that both bands had become household names to millions of British people.

“Listeners-in” (initially using headphones), including many of whom had never been near London in their lives, were captivated by the metropolitan sounds of tinkling tea cups and wine glasses and buzz of talk behind the ultra-modern syncopated rhythm of the music.

Jones’s voice must have frequently contributed to the general hubbub heard by the wireless listeners. He liked the Savoy and felt comfortable amongst its famous guests. He gave frequent dinner parties in its restaurants, entertaining friends, business associates and clients of Reuters.

So far as Jones was concerned, it was during the early years of the Second World War that the Savoy supremely came into its own. In his autobiography A Life in Reuters he tells us that during the autumn of 1940 and well into 1941, when the bombing raids on London were at their most incessant, the absence of transport meant that it was frequently impossible after nightfall to get from Reuters to his home in Knightsbridge. So he took up quarters at the Savoy.

“I thus was sufficiently close to Reuters to be able in between German attacks to grope my way in the black-out (with everlasting steel helmet and gas mask) from Fleet Street to the Savoy (and sometimes back); or at a run, sheltering where possible on the way, when the attacks were prolonged and a dash had to be made. I have a memory of the blazing nights when the Strand Churches... were wrecked, when St Bride’s alongside our overshadowing Reuters-PA building was gutted: when the ancient Temple Church and the Inns of Court that graced the gardens sloping from the Strand to the Thames were devastated, when bombs exploded on the Embankment and pock-marked Cleopatra's Needle; and when they were dropped upon a corner of the fortress-like Savoy itself, reducing to matchwood part of the second floor, on which I slept, and killing the two occupants of the suite next to my bedroom.”

This was his finest hour. For once, there was no pretence, no pomposity. He was risking his life for Reuters and its ideals just as much as any of his war correspondents on the front line.

The wife whom Jones could not reach in Knightsbridge was the popular novelist and playwright Enid Bagnold. In 1944 Hollywood was to turn her novel, National Velvet, into a film starring the young Elizabeth Taylor - who later became a frequent guest at The Savoy. The irony was that his wife’s writing made her into a celebrity, something which Sir Roderick himself never achieved.

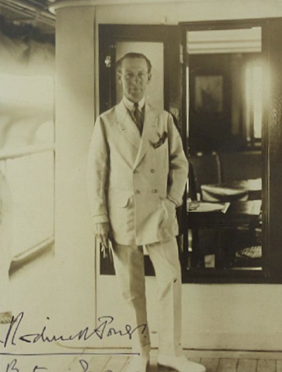

PHOTO: Sir Roderick Jones on board ship during a world tour in 1924. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 19 of 49