Columns

Breaking News revisited

Monday 18 July 2016

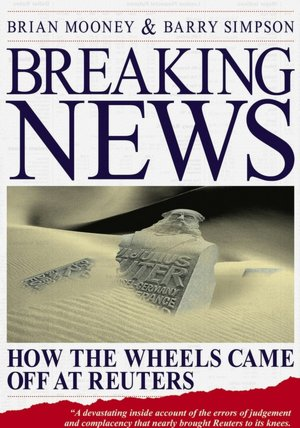

This year marks the 10th anniversary of Barry Simpson’s untimely death at the age of 57 on 24 July 2006 - occasion to recall a fine colleague and to revisit our unexpected joint venture: Breaking News - How the Wheels Came Off at Reuters.

The title was never our choice (the publishers Capstone Wiley insisted on it) but it has served the story well since the book was first published in 2003. Reuters was on the ropes at the time, and not many years later, as we predicted, the brand was sold.

The title was never our choice (the publishers Capstone Wiley insisted on it) but it has served the story well since the book was first published in 2003. Reuters was on the ropes at the time, and not many years later, as we predicted, the brand was sold.

Writing a book with another person is an intimate experience, and I got to know Barry better in those feverish months of researching and editing than I ever did during our joint careers at Reuters; we were both 1971 trainees. He was conscientious, good natured, diligent and dogged. We approached the job as two professionals, and worked together seamlessly and effortlessly.

The book was Barry’s idea. He had long left Reuters, and had gone on to run a media recruitment consultancy, but he retained a great affection for the company, coupled with astonishment that it was in such trouble. I had left more recently, and under a dark cloud, subjected to a “court martial” or disciplinary hearing on my final day because of an alleged leak in the FT which turned out to be sourced on an interview given to the paper by one of our trustees - Per Gyllenhammar. At stake was my early retirement package; not a pleasant way to end a 30-year career.

When Barry called me shortly before Christmas 2002 and suggested the book, I told him about the circumstances of my departure and that the last thing I wished to do was to write any more about the company that I had reported on for several years as editor of Reuters World. But, in an unguarded moment, I said he could contact me if he found a publisher.

Five days later, we were sitting down at a London restaurant with two senior editors from Capstone Wiley.

It is a matter of record that Reuters refused to cooperate - on the face of it an odd thing for a great communications company. In fact company lawyers sent our publishers and us a succession of threatening letters. One senior executive did finally and somewhat begrudgingly see us - but by then the typescript was with the printers, and in any case he didn’t have anything to say that fundamentally altered the story.

It is a matter of record that Reuters refused to cooperate - on the face of it an odd thing for a great communications company. In fact company lawyers sent our publishers and us a succession of threatening letters. One senior executive did finally and somewhat begrudgingly see us - but by then the typescript was with the printers, and in any case he didn’t have anything to say that fundamentally altered the story.

Capstone Wiley duly took note, and we lawyered out some of the more salty accounts of how senior managers behaved at the time - material inserted simply to demonstrate the prevailing culture at the top.

I regret that we didn’t name more names and name more sources. We interviewed many current and ex-Reuter employees, and we were grateful for the widespread cooperation and assistance given to us, but there was a climate of fear, and some who talked to us refused - not surprisingly - to go on record.

My biggest regret is that we did not develop more fully the core thesis that Reuters was an accidental company. The company struck lucky with the conjunction of the surge, post Bretton Woods, in foreign exchange trading and with the simultaneous development of technology which led to Monitor and Dealing and created a new screen-based global marketplace. That generated undreamed of profits which paved the way for the 1984 listing in London and New York and - as we wrote - encouraged a bunch of journalists to believe that they had become bankers. They might argue that they did well, and they may look back with pride at their time at the helm - but the stark truth is that after they departed the brand was sold by an ex-mergers and acquisitions lawyer from New York, and 157 years of staunchly fought-for independence was over.

Did the merger in the end make any difference?

That never-to-be-repeated FX-driven bonanza also bred a top-down approach to the markets, and an unparalleled degree of company arrogance, and an over-dependence on earnings from foreign exchange services. Bloomberg’s bottom up, market-driven product was built on a much broader base of the financial markets, and Michael Bloomberg kept his offering simple - the Bloomberg Terminal.

Those jumbo earnings gave Reuters cash to go on an acquisitions spree - with mixed results. Many of the acquisitions were badly integrated or just clumsily melted down.

The merger with Thomson leaves Reuters vulnerable to the same fate.

Did the merger in the end make any difference?

The old Reuters guard were cleaned out and some things were transformed, but in several key respects not a great deal changed.

Top management appears to have maintained its practice of awkward lurches and abrupt changes. On the trading floor, Eikon, the primary platform which succeeded Armstrong, was no runaway success. Editorial set off on a roller coaster, heading for the stars with Reuters Next and then plummeting back to Earth; all the time its cost base increasing so fast that news services are now partly subsidised by commercial sponsorship. For all of its superior functionality, Reuters Messaging has never caught up with Bloomberg’s Chat. And while there were strategic disposals, Thomson Reuters also continued enthusiastically down the acquisitions trail.

But perhaps the biggest measure of how things haven’t really changed is that in 2008, at the time of the merger, both Reuters and Thomson forecast that their combined services would give them the edge over Bloomberg in the financial data market.

Far from it. Bloomberg has in fact not only kept ahead but actually widened its lead over Thomson Reuters. According to recent market estimates, there are some 325,000 Bloomberg Terminals installed worldwide, compared with around 210,000 Thomson Reuters Eikons.

There has been more than enough drama and intrigue for a sequel to Breaking News - not least in the tribulations of editorial where the old news agency seems to have all but disappeared.

Could the story have ended differently?

Breaking News highlighted muddled thinking, a shortage of strategy, failure of imagination and poverty of ambition - a reluctance to “follow the cable” and take the next big bold step. The chairman at the time, Sir Christopher Hogg, was even proud that he had kept the money under the mattress.

This is nowhere near the complete answer, but what, for instance, could have happened if Reuters had developed a Google-type search engine, or bought Google or even become Google?

PHOTO: Brian Mooney (right) with Barry Simpson at the latter’s home in France in 2006 shortly before in died.

- « Previous

- Next »

- 20 of 65