Comment

David Kaye

Thursday 12 January 2023

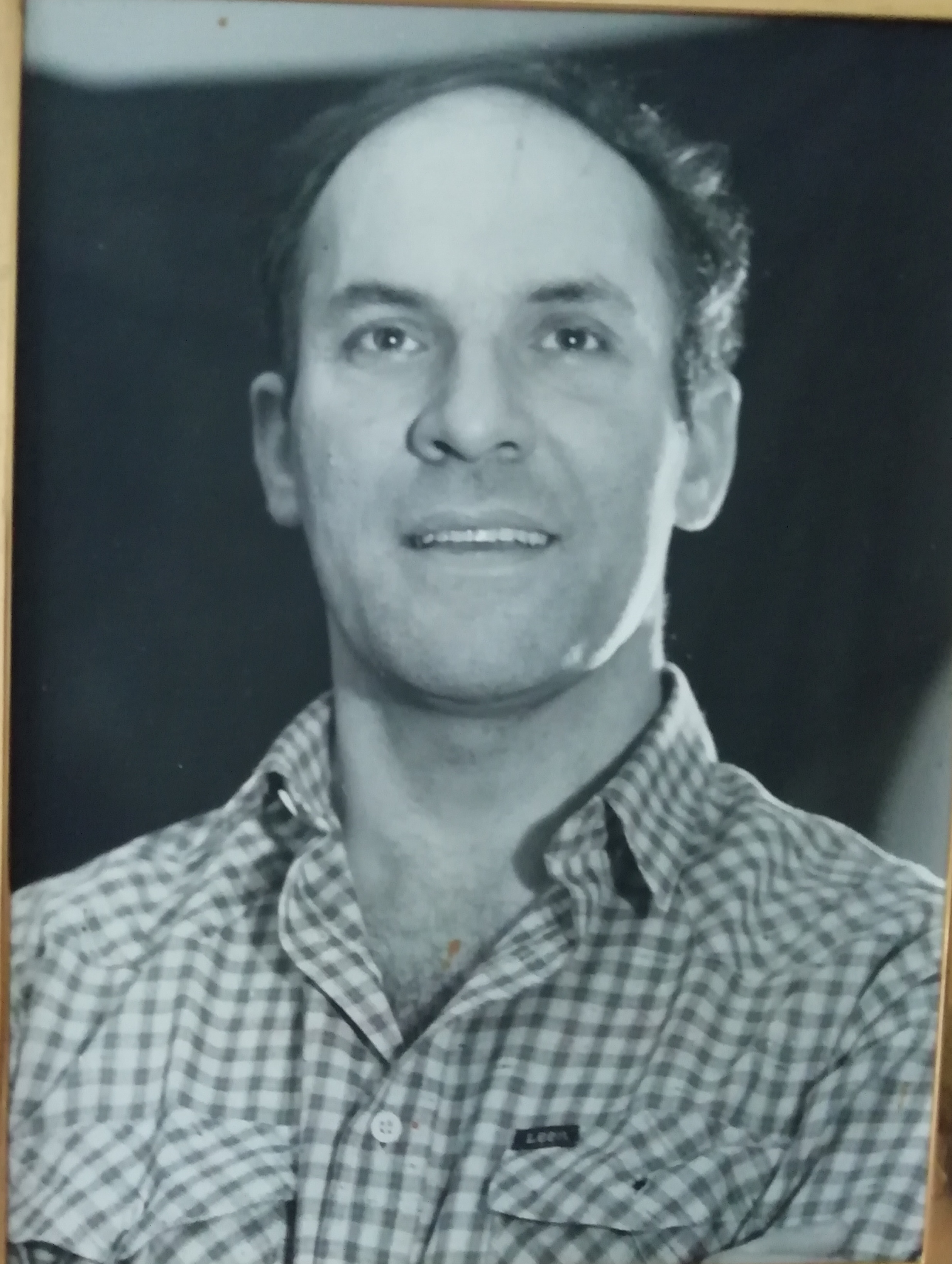

Please pause to honour the memory of my late, beloved husband David Kaye (pictured at age 39), who succumbed to complications arising from Parkinson’s Disease on 17 June 2022 at the age of 82.

Please pause to honour the memory of my late, beloved husband David Kaye (pictured at age 39), who succumbed to complications arising from Parkinson’s Disease on 17 June 2022 at the age of 82.

David’s career with Reuters was marked by unfailing excellence and commitment to the company’s aims and ethos, and I feel I may fairly claim that his skills, insights and commitment helped drive the company into great technical achievement and prosperity over the latter half of the 20th Century. The work he completed during his 22 years in Reuters is outlined below for the benefit of those who did not have the privilege of knowing him, or who have forgotten him.

David joined Reuters Ltd London in 1969 as a computer engineer after having spent five years in the RAF as a radar engineer/fitter covering all ground-based secondary radar systems, followed by employment with ICT (now ICL), where he developed and polished his electronic and computer engineering skills before entering Reuters.

David rapidly demonstrated his ability and developed into the company’s de facto Message Switching specialist, leading a team of engineers charged with its maintenance, modification, expansion, improvement, installation and commissioning. He remained in this role until 1979, assuming further duties along the way.

In 1972 David took on the role of editorial/communications supervisor responsible for Reuters Editorial Systems, and in 1974 he further assumed responsibility for the smooth running of communications systems at Reuters Head Office, supervising a staff of 25 engineers, including three section heads with responsibility for editorial systems (two types of message switching computers, which were maintained to an availability of 99.9%), communications (several TDM and FDM systems feeding Reuters’ numerous network lines), and peripherals (electronic printers, tape readers, selectors, keyboards, repeaters and a considerable distribution function to and from PTT lines, among others), respectively. The systems were maintained around the clock.

In 1977 the first in-house Reuters video-editing system was being developed in Fleet Street, and David was detached from his existing duties to assist the development department. After six months he was also asked to coordinate the project and its team of programmers and engineers. The equipment for the project was uniquely tailored to Reuter requirements. David completed the first news desk installation at the end of 1978, launching an ongoing programme of development and installations that was to continue into the 1990s. The systems David had helped to develop were installed as far afield as Hong Kong, and served temporarily at Moscow, facilitating Reuters’ coverage of the 1980 Olympics.

In 1979 David was asked to join the Exchange Dealing Project as its project coordinator. This system used DEC equipment - to begin with, two PDP11/70 and ten PDP 11/34 processors plus an initial number of 160 PDP8/420A terminal controllers - and was the outcome of merging two large in-house projects: Dealing and Software Multiplexing (an early, inhouse-developed form of packet switching, which was put to use to carry the Dealing Service’s inter-node communications. Dealing was a communications breakthrough in that it was the first global, fully interactive conversational multi-terminal system to offer a variety of hands-on client services direct to subscribers. David’s chief task on this huge project was to ensure it finally went “live” after having suffered various delays due to technical and logistical difficulties. David solved these by means of rigorous critical path analysis and implementation, liaising closely with each of the many groups and teams involved in the development, installation and testing of the system both in London HQ and the European data centres to which it was initially deployed. Both his operational experience and enthusiastic technical input lent the impetus required to launch the project, which went live to clients in February 1981.

In 1982 David was again asked to help with an ambitious new development: the transfer of all the major Reuter systems onto a satellite-based data network (yet again the first of its kind) which drew heavily on his technical expertise and knowledge of operational requirements. The network would ultimately feed data to more than 70,000 terminals.

In 1985 David was promoted to the post of technical project coordinator for a major new editorial system costing $5 million, which integrated both video-editing and message switching facilities for over 150 terminals and 200 lines. The suite of facilities it offered included Autotelex, Interactive Dial-up, X25 PSS, Kilostream X25 Newsbank (Batelle) database connections (another first), and a Reuters Monitor System connection. David went on to provide expert technical support for the system to all European editorial systems and teams. The service extended around the globe with installations as far afield as Nairobi, where David introduced the editorial equipment in 1987.

From 1988 onwards, David continued to provide technical support for Reuters continental editorial systems, with particular emphasis on technical troubleshooting and monitoring systems’ performance and life expectancy. He was also responsible for the global technical support of Reuters editorial systems, which he conducted from within a newly formed development group tasked with the introduction of new global messaging formats across all systems, among other roles.

In 1990 David realised a long-cherished ambition when with Reuters’ approval he enrolled on a day release-based MSc in Communications Science and Technology with City University. He graduated in 1991, having completed a comprehensive survey of Reuters editorial systems and their users as the basis of his Master’s thesis. This prized award was particularly gratifying because he stemmed from a low socio-economic background and his grimly defeatist working-class parents, who had not shared his enthusiasm for education and decried his desire to study on past primary school, had blocked his wish to enter formal secondary education. This had forced him to self-study for his secondary school certificates in science and technology. Aged 16, by dint of solid application and determination over five years of working in a factory by day and “swotting” by night, David had finally won his Secondary School “O” Level Certificates.

In 1991, fate intervened and toppled the applecart of David’s Reuter career when I fell ill (David and I had met and fallen in love on the Dealing Project for which I was the Zürich-based quality control and project testing coordinator in Switzerland, and we had married in 1981). David felt compelled to seek voluntary redundancy from Reuters. My illness was so grave as to render recovery problematic, and he was determined to make sure that our two young children should suffer as little as possible if I died. (Fortunately, however, we were spared the worst, and David and I went on to enjoy a further 31 devoted and laughter-filled years together). Despite the life-changing impact of this event on his prospects, David assumed the roles of housekeeper, cook, loving father/carer and nurse without complaint, and soldiered on for over a year until I was declared fully out of danger and allowed to resume a more active life. Even more remarkable is the fact that despite his many duties in loco matris, David somehow found time to pursue his own interests in computer graphics, worked on creating a reliable random number generator, experimented with the creation of a program that simulated human interactions, and programmed computer-based cosmological models (he was a life-long amateur astronomer and cosmologist, having hand-built his first telescope while he was still a teenager). Like his great hero Alan Turing, David also thoroughly enjoyed solving abstruse puzzles, and was invited to join Mensa after completing one of their newspaper tests for fun and sending it in, only to find that he had a measured IQ of 170. This amused him enormously. His passion for puzzles and debate gave rise to many stimulating and instructive family discussions, as well as a cherished family ritual: every Christmas our son would present him with ever more challenging problems, and he would amaze and delight us by completing each in record time.

David was that rare being: a fiercely intelligent, stoical, cheerful, efficient and hardworking, all-round hands-on electronic, hardware and software computer engineer, whose ability to master every system he encountered was exceptional. He earned a well-deserved reputation both in England and abroad for his enthusiastic completion of every task to which he was assigned, meeting tight deadlines with a minimum of obfuscation or bother, and delivering project after project within budget. He was unfailingly good-humoured, patient and generous with both his time and help, benignly shepherding younger colleagues through the challenges of the complex and ever-changing Reuter technical landscape. And he did it all without expecting special reward, recognition or kudos. His ethos may be summed up as “do it now, do it well, and don’t make a fuss”. He never took himself too seriously, and ran his teams with a light touch, leading by example and giving unfailing respect to every individual he met, regardless of their gender, race, religion, age or other status.

Of course David had dislikes. He could not abide xenophobia, humbug, gossip, “sloppy thinking” and people who blew their own trumpet and/or failed to show due respect for others. He only ever drank sparingly, and was not easily lured into long wet lunches or suppers with colleagues (apart from the occasional after-work pint at The Sutton Arms or celebratory drinks on the successful completion of a project), because his home and family came first. The people who worked with him respected and liked him despite his refusal to carouse, knowing that his quiet, largely self-forgetful presence harboured a razor-sharp intellect coupled with oceanic benevolence and a delightful sense of humour. His abhorrence of self-advertisement extended to the way he conducted campaigns in support of the environment, the Green Party and a variety of charities such as Amnesty International, for whom he completed a great deal of solid, practical work steadily, efficiently and quietly.

To us, his fortunate family, David was a devoted, light-hearted, stoical and considerate husband and father to our children, whose efforts and achievements he enthusiastically encouraged and celebrated. Even when he was heavily engaged in a Reuter project, we never doubted that we held the first place in his heart. It was typical of the man that he declined several offers of overseas postings and promotions because he was unwilling to jeopardise our stability and contentment. Far from regretting the consequences of putting his loved ones before his own career, he was content to remain active in the technical and engineering functions for which his skills so eminently suited him. Not only had he made his own fortune despite being born into extreme deprivation, but with his steadfast and determined efforts he also ensured that our children would never suffer the disadvantages of a poverty-stricken or determinedly underachieving family environment. This, to my mind, constitutes his most praiseworthy achievement of all.

In line with his wishes, David was laid to rest on 5 July last year in a woodland grave overlooking Cambridge University’s Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory at Barton. Only our daughter Gianna, son Simon, their partners and I attended the simple ceremony, and a single bouquet of flowers from our garden decorated his coffin. As I said, he hated a fuss. But despite that, I have decided that he deserves to be remembered in The Baron, which represents the company he was proud to serve loyally for so many years.

The epitaph chosen by our children for his memorial plaque reads “A beloved husband and father, who left the world a better place”.

He will forever be bitterly missed by us all. Requiescat in Pace. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 142 of 1808