Library

Battles, bottles and bastards

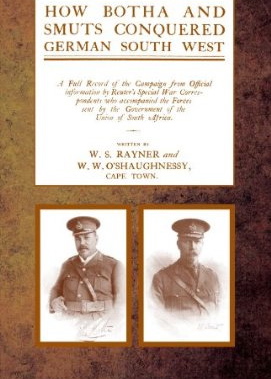

WS RAYNER & WW O'SHAUGHNESSY - How Botha and Smuts Conquered German South West: A Full Report of the Campaign from Official information by Reuter's Special War Correspondents who accompanied the Forces sent by the Government of the Union of South Africa - Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent - 1916

“Small War in Africa - Not Many Dead” might well sum up the 1914-15 campaign in which South African forces drove German colonialists out of South West Africa, now Namibia. It certainly ranks as one of the more obscure sideshows to the main World War I event on the Western Front.

“Small War in Africa - Not Many Dead” might well sum up the 1914-15 campaign in which South African forces drove German colonialists out of South West Africa, now Namibia. It certainly ranks as one of the more obscure sideshows to the main World War I event on the Western Front.

That said, there are reasons why Reuters people past and present might be interested in the book written about that campaign and entitled How Botha and Smuts Conquered German South West. For a start its joint authors were Reuters correspondents, WS Rayner and WW O’Shaughnessy. They wrote the book after covering the campaign up close and personal - they were an early example of embedded journalists. The account of the campaign is laced with descriptions of the attendant frustrations of being embedded, including dealing with cretinous censors, which will resonate with their modern counterparts. Another issue - that embedded reporters tend to side with their hosts and lack impartiality - was not a problem for our intrepid duo, who made no secret of their belief that the Germans were “our enemy”.

Nevertheless Rayner and O’Shaughnessy were top-class reporters. Aside from some passages of ponderous detail, the book is an absorbing read. The authors show a fine eye for colour, with a rich fund of entertaining and often bizarre anecdotes, to embellish their accounts of the combat in this starkly beautiful corner of Africa.

The heavily outnumbered Germans didn’t stand much of a chance and appeared to be resigned to defeat - or worse. One German prisoner enquired of his captors when he could expect to be shot (he wasn’t). The “not many dead” included 122 on the South African side, recorded in separate British- and Dutch-descent categories, a reminder that they were at each other’s throats little more than a decade previously in the Boer War.

The many pleasures of this book include high-quality illustrations, including a photograph captioned Souvenirs of a German Camp, which portrays nothing but an impressive array of interesting-looking bottles. Incongruously for a book about war, there are also breezy advertisements promoting the delights of life in the region: “Rhodesia - Land of Sunshine. Within 21 Days of the UK”.

This being about early 20th century South Africa, the black majority gets scant and mostly patronising reference. It’s only on page 261 that we learn that the South African forces recruited as labourers no less than 25,000 “natives”, who are loftily commended for their “inimitable manipulation of draught animals”.

There are also intriguing mentions of a group of mixed race settlers in South West Africa who are called, officially and with a straight face, the Bastards - which indeed is what they were, at least originally, being the offspring of white men and African women. (Whatever happened to those Bastards? I hear you ask. To find out, Google basters).

I found my 1916 edition of this fascinating chronicle in Cape Town in 1990, the year Namibia gained its independence and vestiges of German colonial rule were swept away (the main street of the capital Windhoek was until then still called Kaiser Strasse). Happily, reprints of the book have recently appeared. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 5 of 22