People

Reuters Middle East boot camp

Sunday 21 March 2021

Readers sometimes tell me the title of my book, Dining with al-Qaeda, gives a showy wrong impression. (Indeed, my first choice was Mr Q., I Love You, but my publisher thought that might be misleading too.) The winning choice derives from my account of an encounter with a Saudi missionary who’d served in al-Qaeda’s camp in Afghanistan, and who had at first declared a wish to kill me. But the book isn’t that much about al-Qaeda at all.

In fact, what drove me to write the book is the second half of the title, Making Sense of the Middle East. This is what I began to learn as a cub reporter for Reuters during six heady years in the 1980s, when I took the Baron’s shilling to report on Lebanon, Iran, Turkey and Sudan, not to mention briefer excursions to Malta, Cyprus, Bulgaria and Yemen. Agency discipline taught me much more about what makes countries tick than my Oriental Studies course at university: how to judge who to believe, quote things accurately, keep the writing short and get the story out, even if that meant dismantling hotel room phone plugs to get at the bare wires with a pair of crocodile clips.

I learned the trade alongside Reuters reporters I admired most, consummate Arabic speakers like Jonathan Wright and Alistair Lyon, the world’s nicest bureau chief Alan Philps, the stylist Andrew Tarnowski, the man of mystery John Fullerton and many others. It is surprising now to think how few women were in Reuters then, but one memorable pioneer was unflappable Kate Dourian. And floating above us all, the benign François Duriaud, the late hierarch of the news agency world who hired me in Beirut.

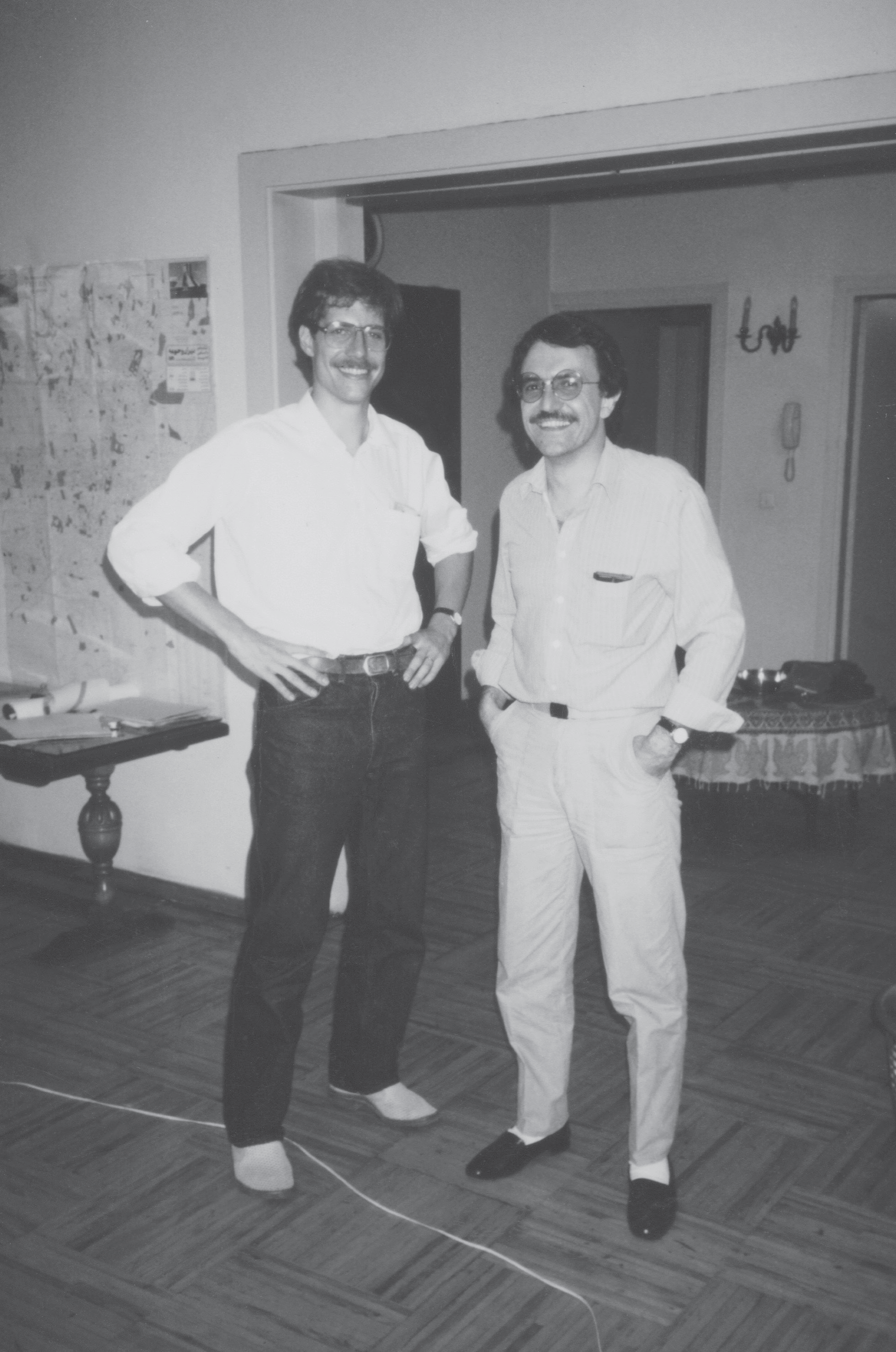

A year later, François posted me to Tehran. Just 25 years old, I stayed for an amazing year, for months the only Western correspondent in post-revolutionary Iran. I’d never have managed without the careful and erudite guidance of Reuters colleague Mohammad Zargham, whose whimsical humour became the lens through which I saw post-revolutionary Iranian politics. He had the idea that saved me from my first expulsion - we drove to Qom together in the office Paykan car to slip a low-bowing letter of apology under the door of the home of an ayatollah I’d been deemed to have insulted - but even he couldn’t have made up one exotic reason given for my second and final expulsion, an official letter that said my sin was to portray Iran as if “the glass was half empty when it was actually half full”.

A year later, François posted me to Tehran. Just 25 years old, I stayed for an amazing year, for months the only Western correspondent in post-revolutionary Iran. I’d never have managed without the careful and erudite guidance of Reuters colleague Mohammad Zargham, whose whimsical humour became the lens through which I saw post-revolutionary Iranian politics. He had the idea that saved me from my first expulsion - we drove to Qom together in the office Paykan car to slip a low-bowing letter of apology under the door of the home of an ayatollah I’d been deemed to have insulted - but even he couldn’t have made up one exotic reason given for my second and final expulsion, an official letter that said my sin was to portray Iran as if “the glass was half empty when it was actually half full”.

Undaunted, François sent me on to Khartoum. Searching for something more to write about there, I asked if I could fly to the edge of the world in Wau, a place so remote it seemed a map of Africa might balance there if it was put on a pin. I still have his telex giving me the green light, basically saying PROPOPE EXDURIAUD (WAU) FINE. As usual, there's not a word surplus to requirements. Perhaps his taciturn side was the result of all those late nights spent clipping excess verbiage from so many reporters’ dispatches. Indeed, I never quite worked out if being sent to Sudan was a punishment for my expulsion from a key Reuters outpost or a compensation prize.

Unfortunately, I then got trapped in Wau for 10 weeks when rebel forces surrounded and besieged the town. François was a pillar of strength while I was stuck and generous when I escaped. He was not all reserve: one evening he invited me round to his house in Bahrain, I still remember how playfully and enthusiastically he picked up a pair of wooden spoons and posed a rhetorical question about salads that has stayed with me ever since: "Une salade, pour rafraichir?"

After leaving Reuters in Istanbul I did spells as a freelancer, as a stringer for the Independent, and finally a decade as a staff reporter for The Wall Street Journal. Writing for newspapers was liberating at first, but the bar to win and keep editors’ attention always seemed to be getting higher.

Symbols of the old news-gatherer’s craft like the once all-important dateline - now a barely noticed afterthought - had already begun to erode while I was at Reuters. Sent back to Tehran for Imam Khomeini’s funeral in 1989, I was swept away by crowds and ended up trapped in the surging throng at his graveside. I was an astonished witness as a Toyota Landcruiser forced its way past and grief-stricken mourners tore at the grey-bearded figure’s burial shroud until his body was almost naked. Hours of walking later, I struggled back to the hotel, booked an international call and, exhausted, began to describe what I thought was an amazing scoop. “Oh, don’t worry, Hugh! The nightlead has already gone out,” the desk editor said. “We saw it all live on TV”.

When I started writing Dining with al-Qaeda, I thought I’d try to counter what I felt was a growing distance between what I really experienced and what got published. I would just pretend that the reader was at my shoulder as I explained what it was like to track down some stories that seemed to me to epitomise life in the Middle East. This way, perhaps, I could give a truer sense of what people needed to feel than if it was written up as polished analysis.

But trying to be true to what I remembered seeing and hearing was hard. I was puzzled how the more I wrote, the less I used my published stories as my starting point, and the more I went back to the first version I had filed. This was especially true in the case of my writing for The Wall Street Journal. Since I still had all the edited versions, and the messages requesting changes, I tried to track down what had happened. I revered the newspaper and its editing - and still think I was lucky to work there during its golden age - but there was no escaping it. Even though I was never asked to say something that was factually incorrect, I could now see that my stories had actually been pruned of so much context that sometimes they really gave a false impression. For instance, in a long story in which I tried to show American readers why a Palestinian village might resent that a nearby Israeli settlement had taken away their land, their roads and their liberty, the headline impression for the Page One reader was that Jews and Arabs had lived happily here side by side until a Palestinian sniper spoiled it all.

Why was this? My search to understand how these distortions happened became the unexpected leitmotif of the book. It wasn’t just my own work for the WSJ; I re-examined a bruising encounter with the work of the late, flawed genius Robert Fisk; remembered advice from my British agent about how I needed to have a relaxed view of facts if I ever wanted to make it as a travel writer; and looked more broadly at why my stories about the 2003 war in Iraq looked so different from those written by admirable colleagues from American bureaux who embedded with US troops.

So alongside explaining what I really experienced in the Middle East, I found myself also showing how, over time, why Americans and others who can’t travel there may understand little of the region. It was partly because editors worked so hard not to give offence to readers and to keep them reading until the end of our stories, they ended up making sure that we challenged few existing assumptions. Since this has been going on for decades, I felt my reports had just become part of a vicious circle of incomplete information, making it ever harder for people to work out the broader context of what was actually going on and what Middle Eastern countries are really like.

Perhaps the new landscape of mass citizen journalism from the ground will solve the problem, or it will be fixed by the new generation of Middle Eastern journalists who can both speak the region’s languages and write as well as anyone else in English. But it’s also possible that the gap between Western imagination and Middle Eastern reality will just grow wider, as news media does less and less real writing and well-judged editing. Either way, of one thing I am still sure. As I end up saying in the book, “it is the ground-level and often overlooked dispatches of Reuters and the Associated Press that should anchor the footnotes of history, not newspaper rewrites of agency reports.”

PHOTO: Hugh Pope (L) and Mohammad Zargham in the Reuters Tehran bureau, 1985

You can get the new paperback edition of Hugh Pope's Dining with al-Qaeda here. Now the Director of Communications & Outreach at International Crisis Group's Brussels headquarters, he is also the author of Sons of the Conquerors: The Rise of the Turkic World and co-author of Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey. ■

You can get the new paperback edition of Hugh Pope's Dining with al-Qaeda here. Now the Director of Communications & Outreach at International Crisis Group's Brussels headquarters, he is also the author of Sons of the Conquerors: The Rise of the Turkic World and co-author of Turkey Unveiled: A History of Modern Turkey. ■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 112 of 576