People

Le Carré in a hurry

Monday 8 March 2021

A Fleet Street editor once drew up a fantasy British government made up of journalists*. It included two former Reuters correspondents with MI6 links - Frederick Forsyth as Foreign Secretary and John Fullerton as Minister of War in Afghanistan.

A Fleet Street editor once drew up a fantasy British government made up of journalists*. It included two former Reuters correspondents with MI6 links - Frederick Forsyth as Foreign Secretary and John Fullerton as Minister of War in Afghanistan.

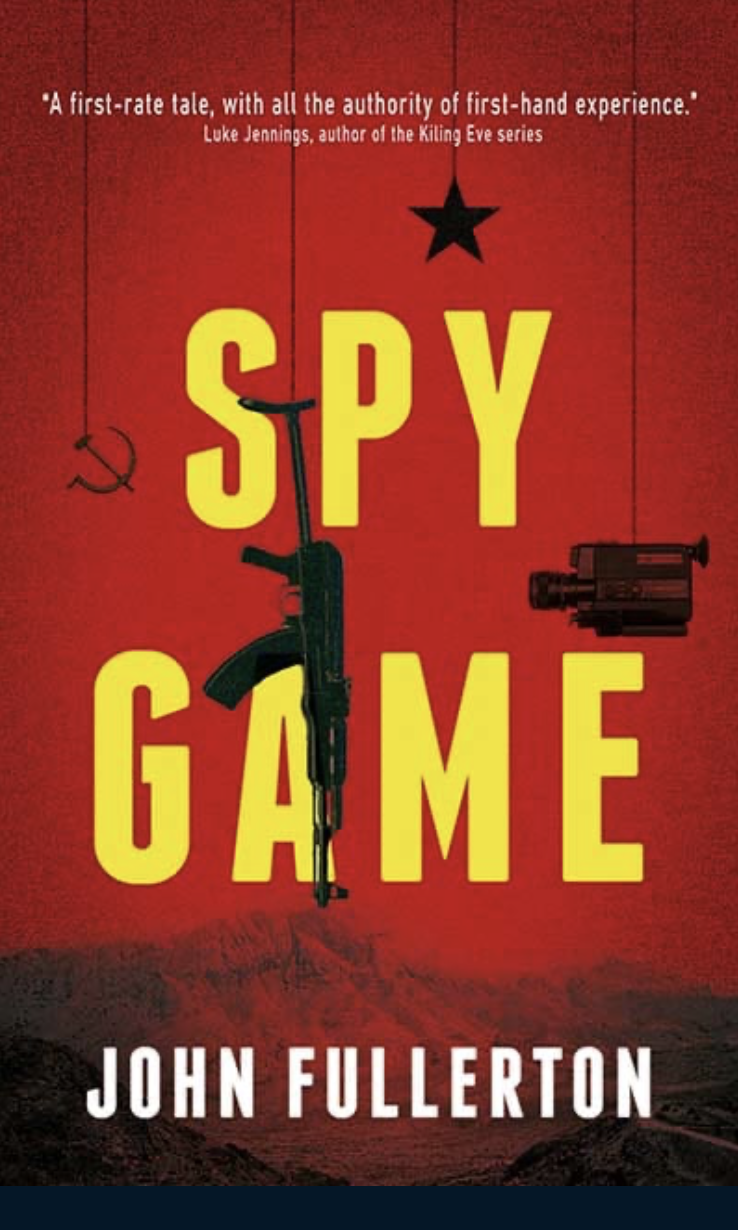

Fullerton was once a contract worker for the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) on the Afghan-Pakistan border and published a non-fiction book, The Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan, in 1983. During our time together on the Reuters World Desk in London, he never talked about his former job but there are clues in his latest novel Spy Game which came out this month.

Spy Game tells the story of Richard Brodick, a novice British “head agent” posing as a freelance journalist. His real job is intelligence-gathering and propaganda. He recruits, trains and pays young Afghans equipped with Super-8 cine cameras to film the Soviet occupation of their country for Western TV viewers and whip up support for Afghan resistance groups.

The sights and smells of Peshawar, capital of Pakistan’s North West Frontier province, are vividly captured as well as the paranoia of spies - “every time he left the hotel on foot innumerable pairs of eyes observed his passage.” Buses reek of mutton fat, sweat and dirty feet.

Brodick joins Afghan resistance fighters on a week-long trek through the Hindu Kush into Afghanistan. They are strafed by Soviet helicopter gunships, attacked by ground troops and hide in an underground irrigation system.

He later returns to Afghanistan to smuggle out a Soviet military canister found by the resistance. It could be a chemical or biological weapon. Or it could simply be a large vacuum flask.

Spies and journalists are very different, he notes. “Both were observers. They waited. They stood aside from the battles swirling around them. The spy tried to make sense of it and report back in secret. The journalist shouted it out from the rooftops and got paid for his noisy over-simplifications, his headlines, brazen first paragraphs and by-lines. The first might start or prevent a war, the second would bring in advertising revenue.”

Spies and journalists are very different, he notes. “Both were observers. They waited. They stood aside from the battles swirling around them. The spy tried to make sense of it and report back in secret. The journalist shouted it out from the rooftops and got paid for his noisy over-simplifications, his headlines, brazen first paragraphs and by-lines. The first might start or prevent a war, the second would bring in advertising revenue.”

Afghan guerrilla commanders were clan leaders and smugglers fighting for tribe and profit. The state, Afghan or Pakistani, meant little or nothing to them.

Brodick has a brief affair with a young French doctor who had worked in Afghanistan. “You know the West doesn’t really give a shit about the Afghans, Richard,” she says. “This is all about bleeding the Soviets, outspending them on weaponry and bleeding them from a thousand cuts in Afghanistan.

“No matter that it means encouraging Afghan peasants to do the dying so we can play the game of nations. It’s dishonest, it’s dirty, it’s cruel, it’s murderous and it’s so unnecessary.”

The adventure turns sour for Brodick when he is ordered to kill his best friend, a politically-active former Afghan university professor living in genteel poverty in Peshawar.

A taut thriller in a slim volume, Spy Game is Le Carré in a hurry.

Fullerton said that after his contract work in Peshawar, he offered to become a career SIS officer. He was told he would not be suitable because he “would chafe under the bureaucratic restrictions of a peacetime service”.

So he joined Reuters instead in 1983 and was promptly sent on risky assignments to Beirut and Cairo and then Sarajevo during the 1990s war that tore Yugoslavia apart. Sarajevo produced a successful novel, The Monkey House, about a detective inspector investigating a murder linked to a Bosnian warlord and black marketeer.

The chafing tendency that did not appeal to the SIS made Fullerton an effective journalists’ union leader at Reuters where he once served as Father of the Chapel.

Now 71 and a widower, he lives in Scotland and is writing a sequel to Spy Game. The provisional title? Spy Dragon.

PHOTOS: John Fullerton outside Kandahar in 1982, and the cover of his latest book

- « Previous

- Next »

- 122 of 585