Archives

Old Russia hand's sangfroid - and the mystery of brunch

Thursday 30 March 2017

His name was Guy Beringer - sole Reuters representative in Petrograd (formerly St Petersburg), Russia’s capital, when the first of two revolutions began, one hundred years ago this month.

His name was Guy Beringer - sole Reuters representative in Petrograd (formerly St Petersburg), Russia’s capital, when the first of two revolutions began, one hundred years ago this month.

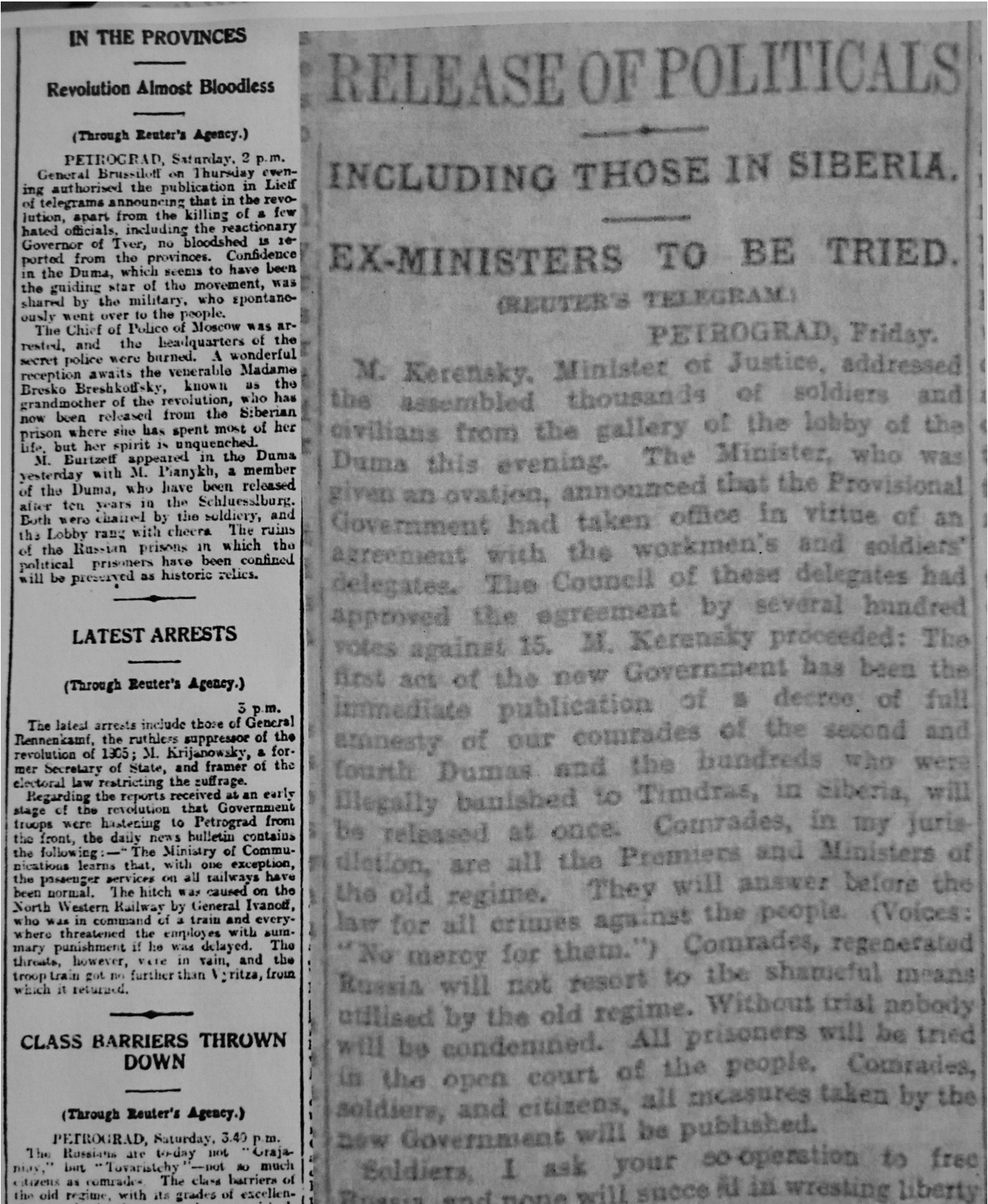

Imperial Russia’s decision to enter the First World War had been a disaster. The fighting cost millions of lives. The winter of 1916/17 was exceptionally cold. Civilians faced mounting food shortages. Fuel started to run short. In March 1917, the Tsar (Emperor) was forced to abdicate. A provisional government made up of former members of the Duma (Parliament) took control - or, at least, endeavoured to.

In Reuters parlance, Beringer was an “old Russia hand”. Accompanied by his wife, he had reported from the city since 1904, when the Russian government ceased to obstruct collection and onward dispatch of internal news by telegraph. He reported on Russia’s disastrous war with Japan. In 1907, he ensured a Reuters scoop, publishing the text of an important Anglo-Russian agreement several hours before its official release.

Events in Russia moved fast. By July 1917, Reuters’ house magazine, The Service Bulletin, rather breathlessly reported the following:

“We have to congratulate Mr. Guy Beringer, our Correspondent in Petrograd upon the really admirable reports which he has sent to us respecting the revolution in Russia. From the moment that the trammels of the Russian Censorship were removed, Mr. Beringer sent forth a perpetual stream of news telling in every detail the whole story of the wonderful upheaval there. Knowing that he would have to meet a very active competition, he dispatched the great mass of his first telegrams at Urgent rates and, thanks to this foresight of his, we were able to receive and publish in our morning papers, and to transmit to all parts of the earth, a most ample and satisfactory account of what had occurred.

“We have to congratulate Mr. Guy Beringer, our Correspondent in Petrograd upon the really admirable reports which he has sent to us respecting the revolution in Russia. From the moment that the trammels of the Russian Censorship were removed, Mr. Beringer sent forth a perpetual stream of news telling in every detail the whole story of the wonderful upheaval there. Knowing that he would have to meet a very active competition, he dispatched the great mass of his first telegrams at Urgent rates and, thanks to this foresight of his, we were able to receive and publish in our morning papers, and to transmit to all parts of the earth, a most ample and satisfactory account of what had occurred.

“The Correspondent who is living in times and in the midst of intense popular excitement is apt to lose something of his own ordinary sangfroid. Mr. Beringer seems to have preserved his coolness from beginning to end and has kept us well and accurately informed of each day’s events and experiences…"

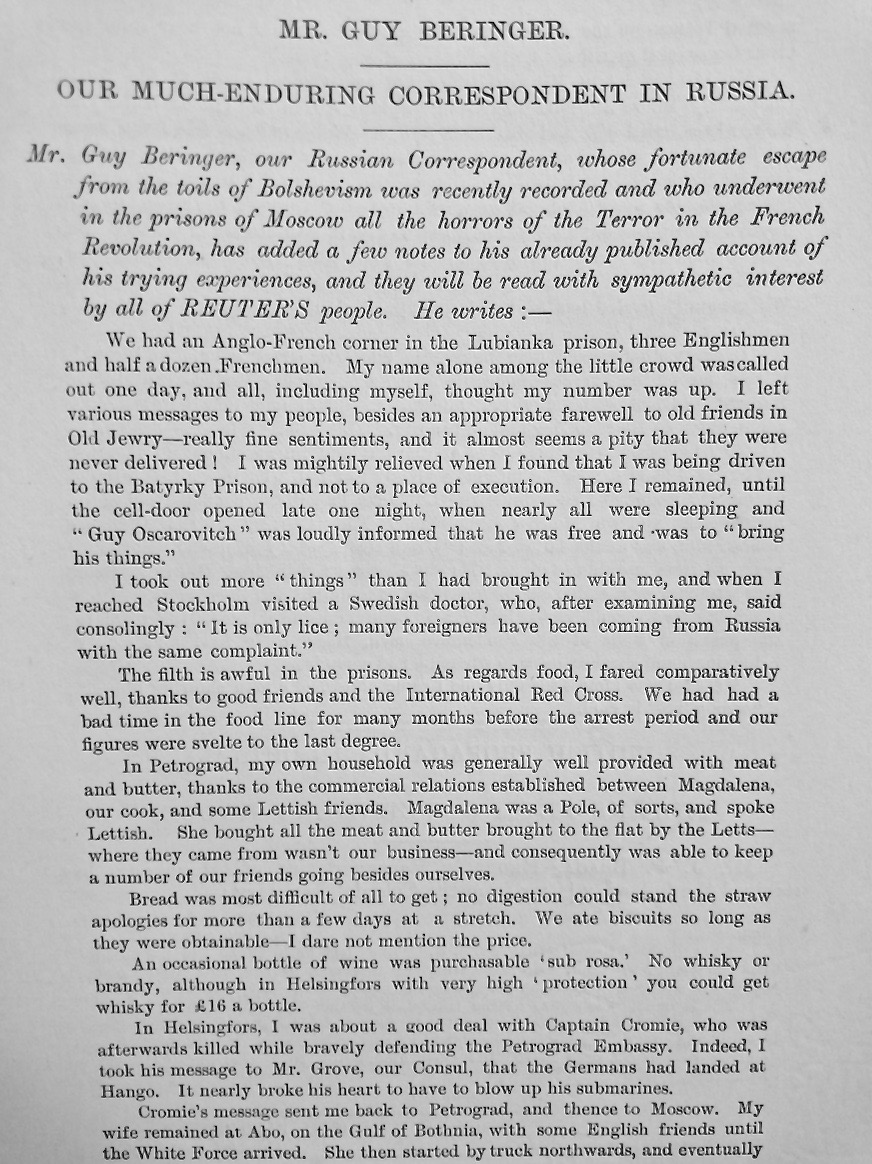

Beringer’s sangfroid was to be stretched even further. By October, the provisional government was sidelined, replaced by the Bolsheviks. Moscow supplanted Petrograd as the Russian capital. Life for the Beringers became increasingly dangerous. Following a short but “challenging” time in Moscow’s Lubianka prison, Beringer was released. He made his way to London and wrote an account of his experiences in The Service Bulletin. Although longer than I would normally reproduce, I think on this occasion, an exception is justified.

A curious footnote: In 1895, a British journalist named Guy Beringer first introduced the name Brunch as an alternative to the heavy, post-church Sunday lunch. “Brunch is cheerful, sociable and inciting” he wrote. “It is talk-compelling. It puts you in good temper, it makes you satisfied with yourself and your fellow beings, it sweeps away the worries and cobwebs of the week.”

Was this “our” Guy Beringer, some nine years before he joined Reuters? It seems plausible. But there is no proof. I know nothing of Beringer’s earlier life and career. Can anyone out there help? If so, I should love to find out more.

■

- « Previous

- Next »

- 46 of 49